This year, at our second Skills Development Conference, I gave a quick speech about micro-aggressions. I quickly talked about what they are, what's the problem, and how I deal with them. I tried to give the topic justice as 2 years prior another ALT gave a similar talk about it, too, and I found it really helpful when dealing with some of the problems of daily life in Japan.

This was part of a session of "micro-panels" which is consisted of 4 shorter talks about various subjects. Subjects not necessarily long enough or useful enough to take over their own 50 minute panel. I budgeted this talk at 10-12 minutes.

I had some help with this presentation, too. Fellow ALT and RPA Cathy Anatra volunteered for this subject, too. Though, I pretty much took over the whole thing, and talked about the things I wanted to talk about. She helped me QA the speech, and gave me some direction and pointers if I was missing anything. She also gave some of her own personal experiences during that part of the talk.

But! Here's what I wrote. This is my intended transcript for my talk. I also included most slides from my powerpoint, and the time-stamps from when I timed myself speaking.

The term "micro-aggressions" carries some baggage with it for those who have heard it before. This is the definition I use: A micro aggression is an everyday slight, indignity, or invalidation unintentionally made towards a marginalized group by a well-intentioned person of the majority. In the case of Japan, the marginalized group would be us.

These actions may seem small, and not even a problem, but day after day, they add up into something greater. They not only make us feel different, but they point out how different we are to the society we are living in. They point out that we don't fit in, and possibly that we won't fit in. We're not the same, and we're outside of their circle.

I'm not talking about directly racist or insulting things, though. I should really underline the terms "unintentionally" and "well-intentioned" in my definition because these are the comments I wish to focus on.

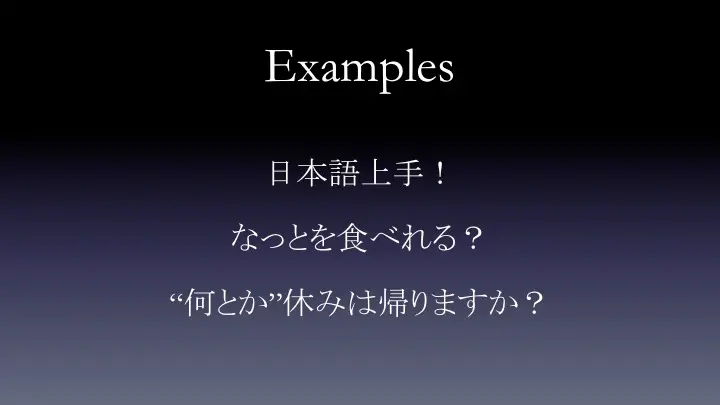

I think the top 3 comments I've gotten over the years have been, "日本語上手!", "なっとを食べれる?", and "何とか休みは帰りますか?". (or) "You're Japanese is so good!", "Can you eat natto?", and "Over the next break, will you go back to your country?" Or even.. "where will you travel?"

We've all heard these haven't we? 日本語上手? Really? I've said 2 poorly constructed sentences, and my Japanese is good? なっとを食べれる? Yes, I can eat natto. Do you think it's poisonous to me, or something? Am I too inferior to eat it? 帰りますか? Will I return? Are you asking because I need to go back to "my people." Because I don't belong here? Because I'm an outsider?

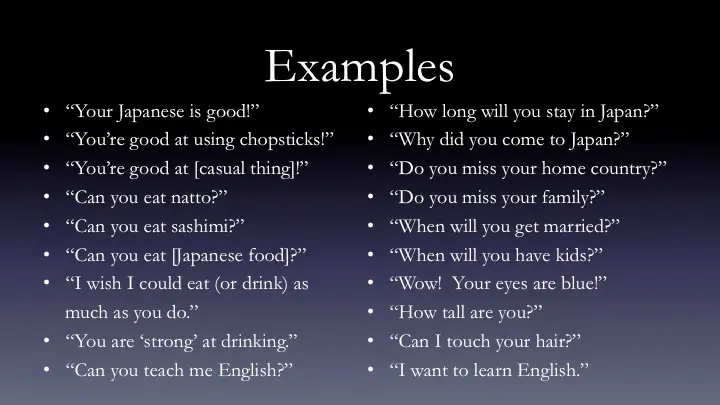

Here are some more examples:

These are the kind of micro-aggressions we all get a daily basis. The first couple of times, it's no big deal, really. But after months and years, they get tiring and their indirect messages become the real conversation.

[2.5 minutes]

Going back to my definition, this is not intentional. The person talking to you is unaware of the underlying message being communicated. They don't "mean" to make us feel alienated, or unwanted with these comments. And this is why it's difficult to confront the "aggressor" about it.

If you confront the other person, and respond to their comments or questions in the same vain as I had just now, you can guarantee they won't make the mistake of talking to you again. You've basically alienated yourself. If you want to go more extreme with this example, perhaps you've now made this person think all westerners are confrontational about the smallest of comments or questions.

However, if you go the other way, by ignoring or shrugging off the comments, you're letting the problem persist. And you've allowed yourself to soak up more of these comments. They build and build, and eventually you revile and hate Japan. If you want to go extreme again, perhaps you'll become a steaming pile of hate whom can never smile, and then no one will talk to you. You've eventually leave Japan, and tell everyone how terrible a country it is.

In both instances, you've alienated yourself, and even created or perpetuated stereotypes.

So.. what's the solution? You are. We are. I think we are the solution.

[1.5 minutes]

For me, I hadn't heard of this term before coming to Japan. I first learned about it at our SDC two years ago. I was at a point where after making friends with some teachers and parents, they made a couple of comments that pushed me back, and made me feel distant. They made me feel like I didn't belong and wouldn't ever belong.

One of the things that turned me around was learning that this word even existed. It gave me comfort, and it gave me strength. This is the reason why I wanted to give this talk, and inform everyone about this word. Knowing about this word allowed me contextualize the comments that were being made, rather than see them as direct assaults against me. And through that I was able to deal with them appropriately.

As an example, at an enkai, one of my teachers kept talking to me in a baby voice. I think we were talking about hiking and mountain climbing, and she kept responding very deliberately and emphatically. It really felt like she was talking down to me. そうですね。すごいですね。Patronizing. 何とか山をのびますか。As if she had to speak this way in order for me to understand.

Even though it annoyed me, I just ignored it, and continued with the conversation. A few minutes later, she began talking with another teacher, and she had the exact same tone. And she continued that way throughout the rest of the night. So it wasn't that she was talking down to me, or anything. That's just the way she talks.

[2 minutes]

Anyways, my solution is not to confront, nor ignore, but to respond in a way that creates a conversation. I think that's one of the most important responsibilities for us in Japan. We should live up to our titles as unofficial cultural ambassadors. We shouldn't directly confront their stereotypes about us, but we should bring them up from time and time, talk about them, and inform the other person about you as a person, rather than you as a race.

Going back to the natto conversation, I just respond with the truth. Eh… it's okay. Nothing special. Do you like natto? How often do you eat natto? What food do you like or hate? I try to pull them into the conversation, rather than it being one-sided.

Going back to the questions, "Over the next break, will you go back to your country?" or "..will you travel?" I really see this more as an icebreaker for small talk. While you could take it as them thinking your life in Japan is just a temporary home, I think a lot of them want to live vicariously through you. They would love to have your "freedom" to travel around Japan, or the world. They want to know more about these places, and how it related to their own lives. And they want to know more about your home country, too.

This was even true at my previous job back in the US. One of my co-workers' spouses said that she loved reading my blog, and looking through all the pictures I posted online from visiting Japan. She liked to live vicariously through me because they don't really travel outside of the country that much.

Both these questions aren't assaults against you because you're different. A lot of the time, many of those examples from earlier are just icebreakers. Other people want to talk to you, and get your opinions on things that may be different for you. It turns into an opportunity for you to inform and educate others about those differences. It's usually a great topic of conversation.

Going back to the baby speech, sometimes if they talk to you like a baby, it could be that they just aren't aware of the amount of Japanese you understand, or perhaps they just don't know how to properly communicate with a foreigner. Talking with them more often, and finding shared interests will give them more exposure to yourself, and to foreigners in general. And make them more comfortable talking to us.

Overall, I would say to put yourselves in their shoes. Think about where they're coming from when making some of these comments.

[3.5 minutes]

Lastly, I think it's important to understand that we can be just as guilty as making micro-aggressive comments or actions as they are. It's important for us as we attempt to defuse micro-aggressions directed towards us, that we in-turn, identify and defuse any that we make ourselves.

I think the two most common ones for me are finding legitimate ways of complimenting or correcting other people's language, and finding ways of talking to Japanese people in English that doesn't sound like Tarzan-speech, or baby speech.

After receiving so many ill-gotten compliments on my Japanese, I never compliment anyone on how well they speak English because I'm too afraid of sounding like they do to me. Though, I have a few teachers that have gotten A LOT better at English since I first met them that probably deserve some kind of compliment or reassurance because of how hard they've tried to get better. I would say that if you were to compliment someone on their English, don't make a single one-off compliment. Tell them why you think it's good, and why you felt you had to compliment them. By giving them the reasons for the comments, it becomes sincere and worthwhile.

As far as talking like a baby, or talking like Tarzan, I think it's very important for us to speak as grammatically and emphatically correct as possible when using English around Japanese people. Adults can definitely tell when they're being talked down to. But for our students, we are the "perfect" model for them to learn correct English. They listen to us way more than you might realize. They have a keen ear for inflection, emphasis, and intonation. If you're "dumbing down" your speech to be more understandable, some of those traits could be accidentally taught to them.

I have an example of this. Sometimes when talking slow, I add unnecessary emphasis on some of my words. Especially, the word "and." One of my students did the speech contest last year. I helped him write the English for his speech, and I recorded myself reading his speech, so he could practice it over and over again at home. I used "and" as a conjunction between two sentences, like so, "So, I think one reason manga is so popular is the choice for readers. And, I think it's fun to cosplay characters that appear in manga."

When speaking at normal speed, the "and" works as intended. It's a soft conjunction joining the two sentences. But, when I slow down, the "and" becomes much more pronounced. It no longer sounds natural or correct if spoken at normal speed.

From that point on, whenever we read something in class that uses "and" as a conjunction, this student always has that extra unnecessary inflection. Weirdly enough, my JTE has started doing it, too.

Again, this example isn't really a micro-aggression in of itself, but an example that your "model" of English, if thought correct, will be imitated. Please keep it in mind.

[4.5 minutes]

Anyway, that's my speech, and that's my advice to you. Thank you. :D

I don't think my talk had the same impact of when I first heard about micro-aggressions, but hopefully it inspired some of the audience members to think about things.

As mentioned before, this was part of a collection of micro-panels at our Skills Development Conference in January. I was the MC for the entire panel, too, so I wrote an additional 3 minute speech to fill time at the end, if needed.

Later this year, I'll give this speech at our farewell enkai for those ALTs leaving the program. It combines two things I've come across talking about foreigners or "outsiders" fitting into Japan.

Enjoy! :D

I have another story about living in Japan, or abroad in general. We are all circle people. We lived in our circle country, spoke our circle language, and hung out with our circle friends. We fit in. Our circle pegs fit perfectly well into the circle holes of our lives.

But now we're in a triangle country. Our circle pegs don't fit into the triangle holes. Being here changes us. We make many conscious and unconscious decisions on a daily basis that changes our circle shape to more closely resemble a triangle. We lose some things, and gain some things. The longer we stay, the more and more we become a triangle. Though, obviously we can never fully be a triangle, but we can make ourselves fit in.

As we return to our circle country, we won't fit in at first. As time goes on, our circle shape will return, but we'll never be as round as we once were. The story finishes by saying we've become a shape that doesn't necessarily fit into either country.

One of my students once wrote a speech on what it was like being half Japanese, and half American living in Japan. Because she felt like she didn't fit in Japanese society, she always considered herself half Japanese. She finally had the chance to visit the US, and while she physically felt like she fit in, she couldn't speak English well, and didn't really fit in there either. She felt half American.

She told this to her grandfather, and he gave her the following advice. He was envious of her position. He never thought of her as half Japanese, or half American, but BOTH Japanese and American. He never saw her as half-anything. She is a double. That really changed the view she had on her own life.

The experiences that we have in Japan, and the changes that happen to us, stay with us well after we leave. They ultimately shape us into the people we will become, or into the people that we are. While perhaps we think we're losing some of ourselves to fit in, we are gaining so much in the process. And we eventually become part of both societies.

[3 minutes]