Over the weekend, I watched Arrival, which is an incredible movie. It’s about aliens coming to Earth, trying to communicate with them, and ultimately understanding why they came. Ultimately how we are able to understand the alien is an idea that is very central to how people learn language and very relevant to me living in Japan and teaching English. I spent 20 to 30 minutes in my junior high classes today talking about this movie and it’s idea.

First, I explained the basic plot of the movie to the students. SPOILERS, yo.

One day, these alien spaceships arrive on Earth. There are 12 in total. One appears in Montana, US. Another appears in Russia, China, and even Hokkaido in Japan. The movie focuses on Louise Banks, portrayed by Amy Adams, who is a linguistics specialist and called upon by the military to communicate with the aliens.

They arrive in Montana and board the spacecraft in a pretty amazing scene with relative gravity and perspective. They approach the aliens separated by a glass window keeping their relative atmospheres apart.

As they approach the glass, they wait. The white atmosphere behind the glass begins to move and circulate. Then the aliens appear through the clouds.

The aliens make some sounds and clicks. In some ways, they sound like the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park, but with a higher sharpness. It sounds very violent, and Amy Adams is quite scared and doesn’t really know where to begin.

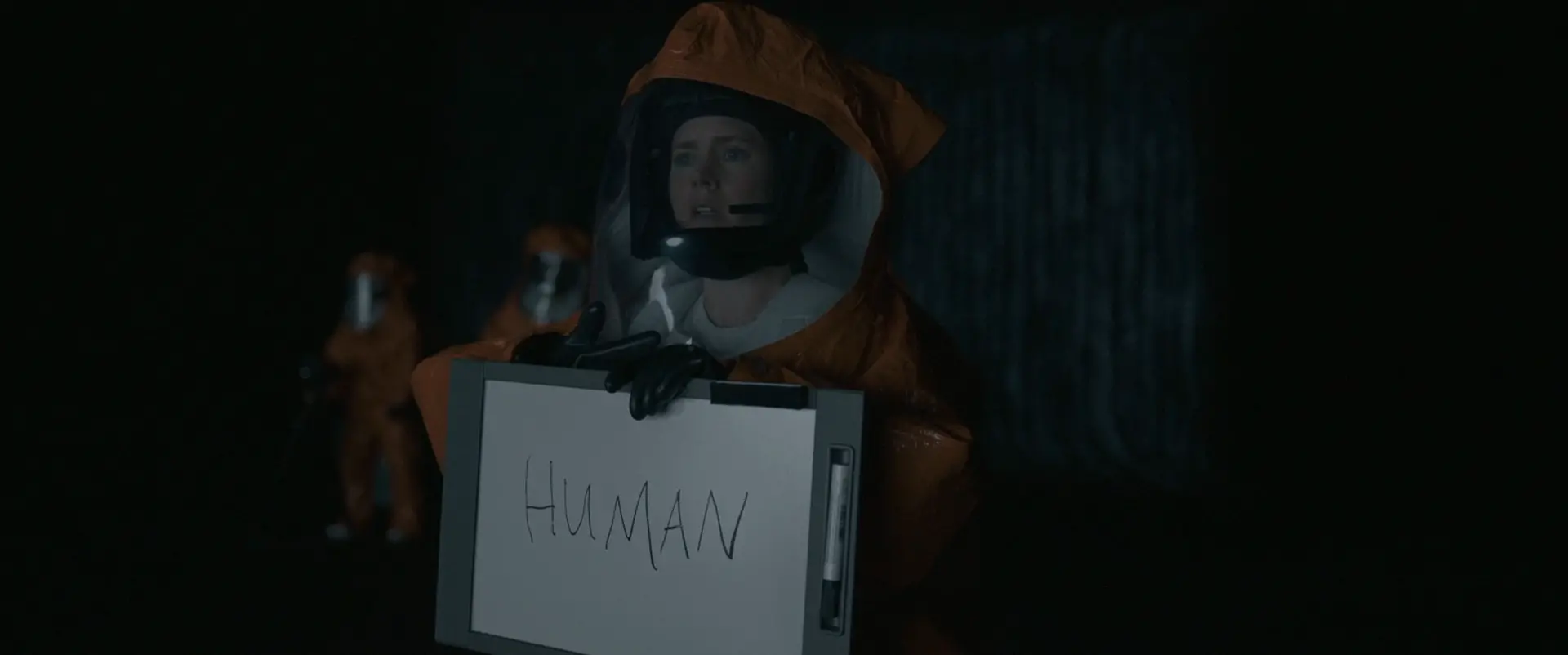

On her second attempt, she gets the idea of using a white board and communicating through written language, rather than spoken.

She writes "human" on her board and shows the aliens while gesturing to herself. The aliens process the information and spit out a word or a sentence of their own.

Over time, Louise continues with more examples and sentences and ultimately understands their language.

Let’s compare their words and sentences to one of our own.

I walk to school everyday.

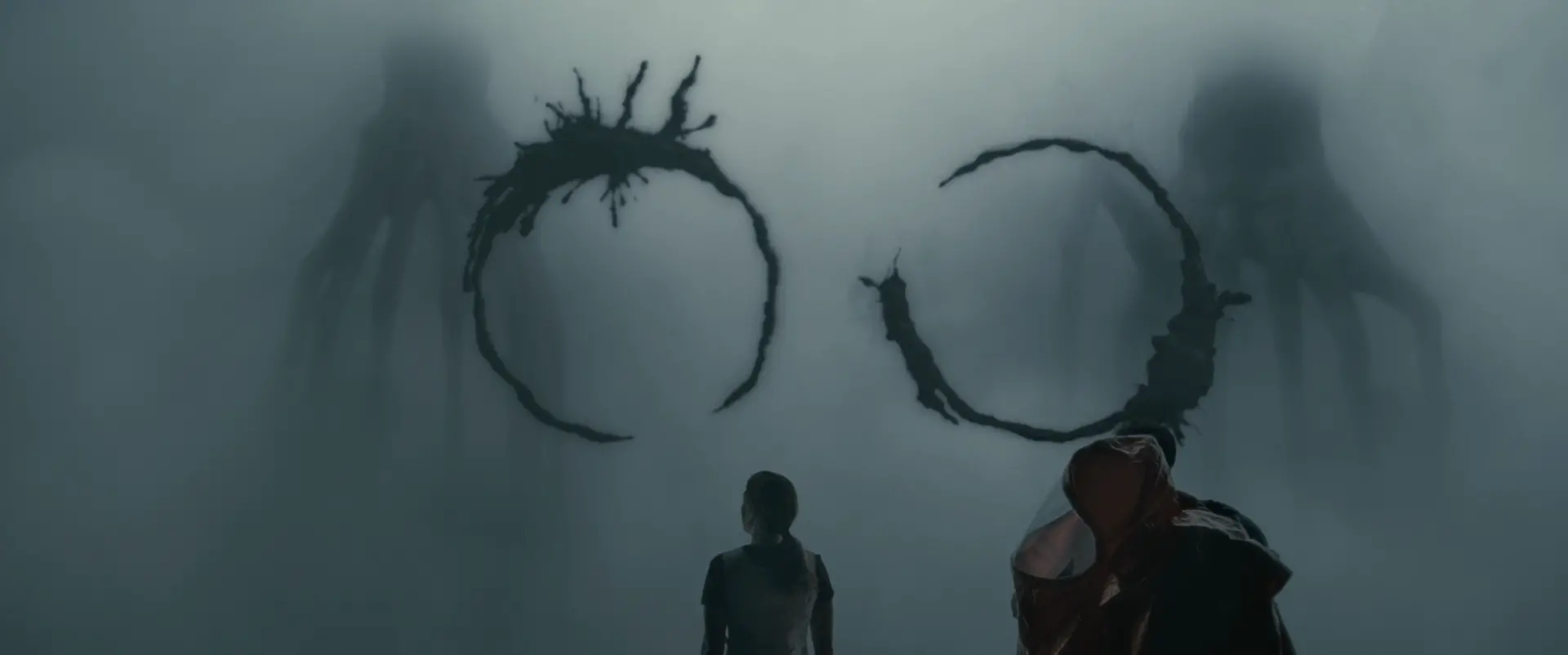

For us, this sentence has a clear start and finish, from left to right. But, for the aliens, their words and sentences are a circle written all at once. There is no start or finish.

From this point when talking with my junior high students, I basically spoil one of the key components of the movie. Later, I spoil the other.

Throughout the movie, we discover this is because the aliens think of time differently. Their perception of time is all at once, rather than a linear line, which is how we think and live in time. At any one point time, they are able to experience all points of time within their lifespan. They know their future and past.

This is reflected in their language. Their sentence is written all at once with no start or finish and words are spread throughout the circle.

As Louise continues to speak with the alien, she begins to understand and learn their language. And through learning the language, her thought process changes, her perception of time begins to change, and she’s able to view parts of her future. Because she’s able to understand and process their language, she’s able to think like them and perceive time like them.

This is the central plot of the movie.

Let’s go back to our previous sentence, and compare it with some other languages.

I walk to school everyday.

Je marche à l'école tous les jours.

Yo camino a la escuela todos los dias.

Ich gehe taglich zur Schule.

There’s English, French, Spanish, and German. Each has its own sound and ring, but the basic sentence structure is the same. I walk. Je marche. Yo camino. Ich gehe.

The very first thing we care about in the sentence is "who" followed immediately by "what is he/she/it doing." After that, everything else is details.

I think this is because our culture, personalities, and attitudes tend to be very direct. Or we tend to favor people and ideas that are very direct. If we can quickly and succinctly communicate the who/what and it’s action, we can understand the idea faster and fuller.

So, how does this compare with Japanese.

私は毎日学校に歩いて行きます。

First is the subject (私 watashi or I), but the verb is the very last thing in the sentence (行きます ikimasu go). All of the other details are explained before the actual actions. I think this is because Japanese language and culture tends to be indirect a lot of the time.

The Japanese teacher in class went on to give some examples of indirectness in Japanese, such as refusing an invitation. In English, when refusing an invitation, we typically say something like, "Sorry, I can’t" or "I’m busy," and then maybe followed by a reason. The refusal can be softer, but typically the first thing we say is very direct, "I can’t."

In Japanese, such directness could be considered rude or harsh, so the polite way to refuse is to be more indirect. "Sorry. On that day, I’ll be out of town" or "Sorry, I already have another engagement on that day." There’s no real reason to say "I can’t" because it’s implied, and because of that those harsh words are never said.

As long as I’ve been learning Japanese, people have always mentioned the idea that they’re able to "switch their brain" when fully immersed in Japanese. They claim they think in Japanese and speaking Japanese becomes more natural to them. Sometimes they need to stop for a second to switch from talking in one language to the other.

This idea is the foundation behind the plot of Arrival. Louise can change switch her brain when communicating in the alien language, and then be able to perceive her current and future memories at a single time.

This has never been the case for me. Over these last 4 years of living here, and 15 years since first learning Japanese, I’ve really just maintained a single mode of thought. My thought process always tends to translate and interpret the incoming Japanese into something I can understand. Outgoing, too, has a quick translation from English to Japanese.

Though, this single mode of thought has changed and been molded over time by all the language and culture I’ve absorbed and learned by living here. For certain kinds of grammar and vocabulary, I can say them pretty fast. It just feels more instinctual rather than a complete switch. Through practice, I feel like I’ve simply trained my brain rather than developed something completely separate.