Since first living in Japan, I became more interested in learning about the war. I learned about how the Japanese people threw themselves into nationalism and made the war more about an attack on their nation's pride rather than about human rights. And I learned about how they suffered as a result. I've seen and learned a lot from the Japanese point of view having visited war sites and museums in Nagasaki, Hiroshima, and Okinawa.

I've never been to any war sites in America. Honestly, we really don't have many at all because we never had any part of our homeland touched by war. Our military bases are still in use, and if they are decommissioned, they are demolished. Our experience in war has almost always been foreign.

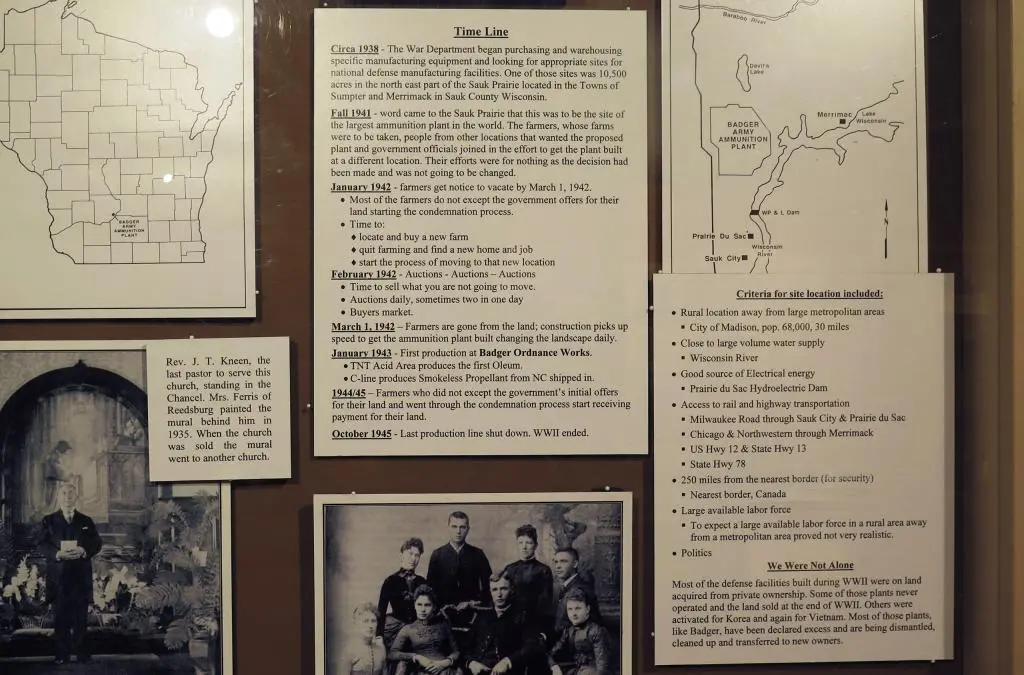

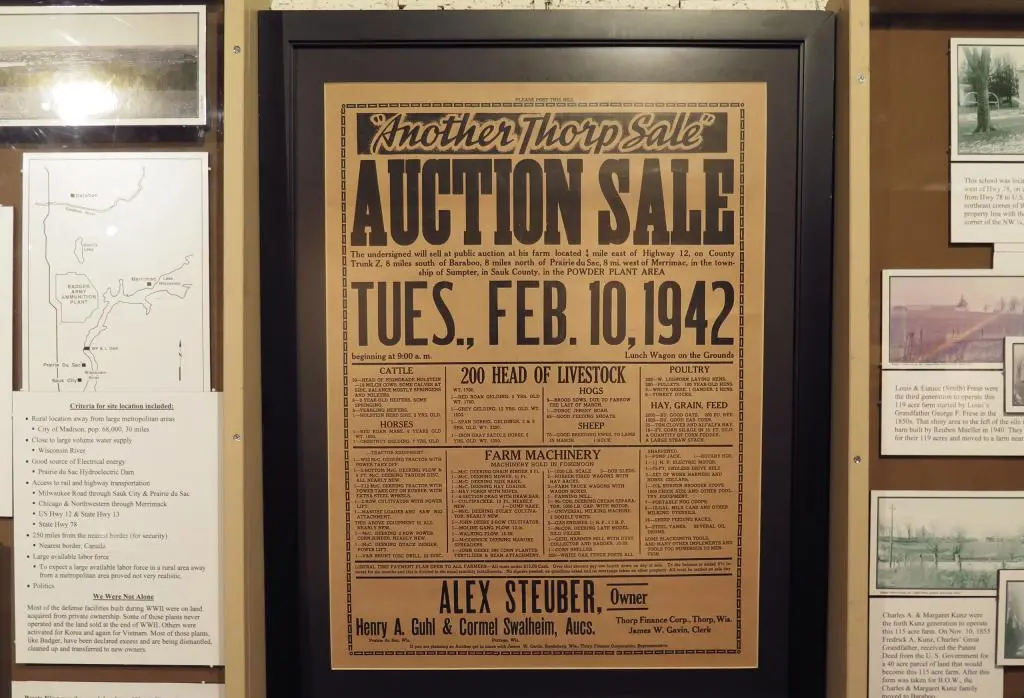

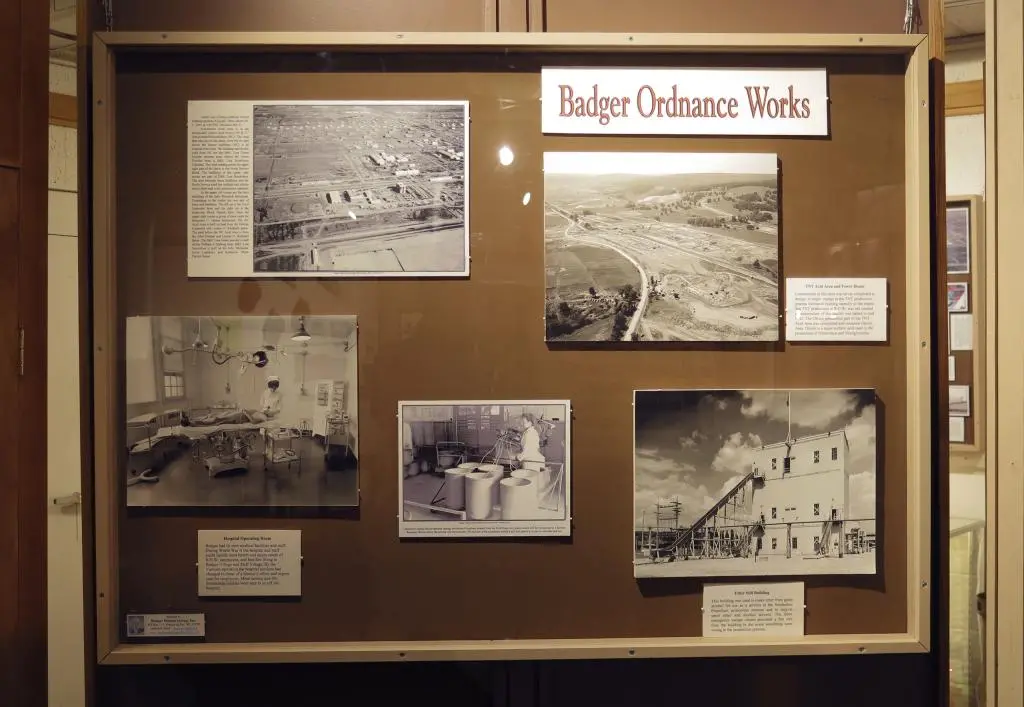

When I was back in the states over summer, I wanted to visit a location I had heard about while living in Madison. The Badger Munitions Factory was a plant near Baraboo to the north that developed and manufactured bullets for our soldiers in World War II.

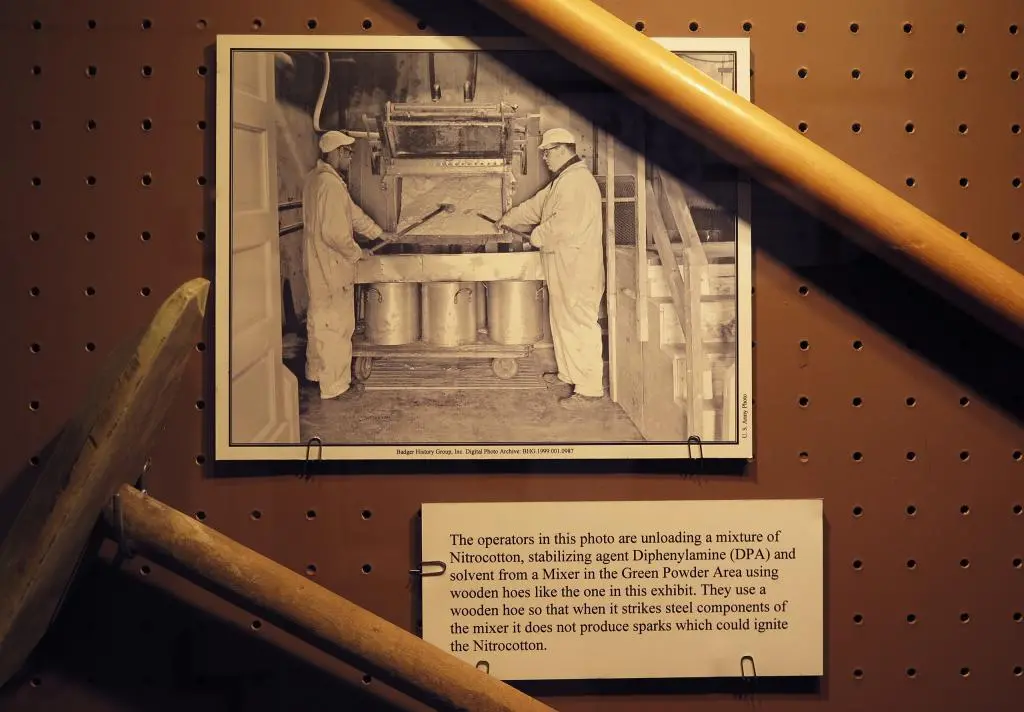

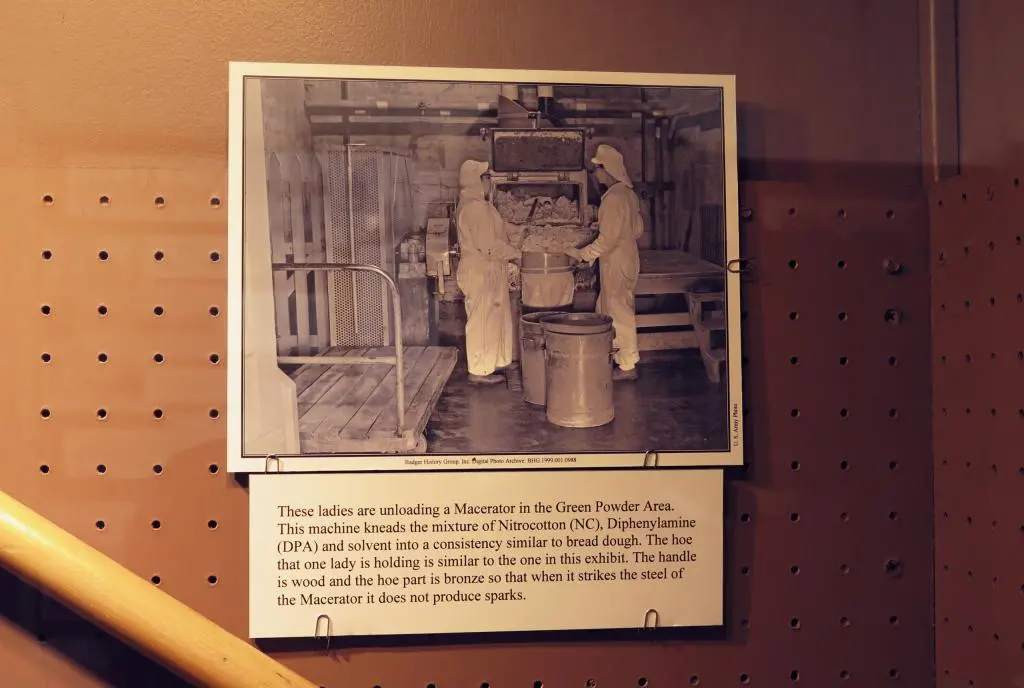

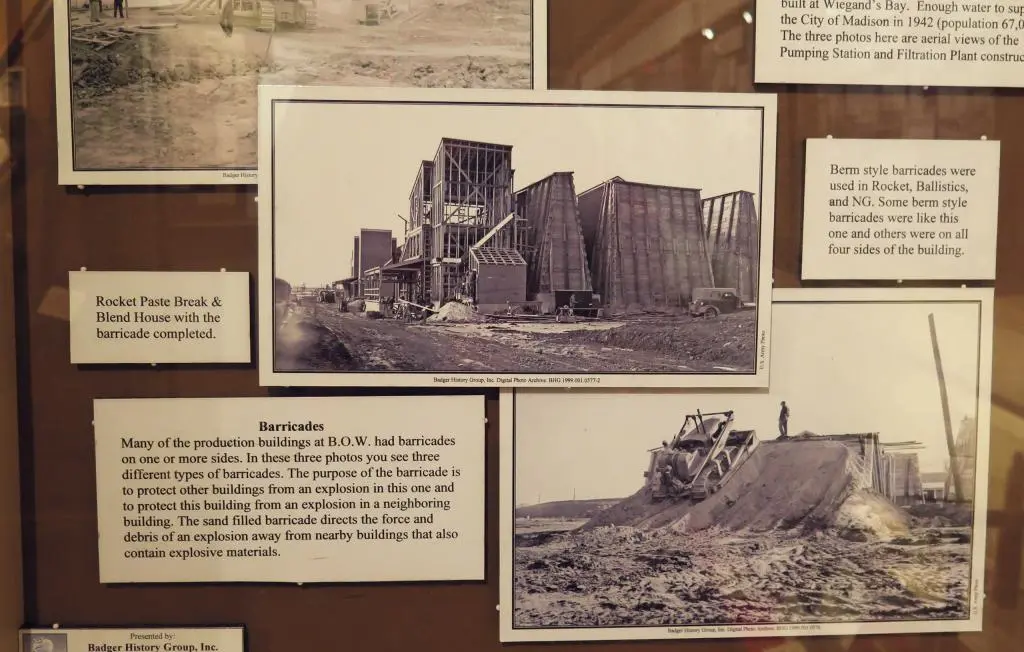

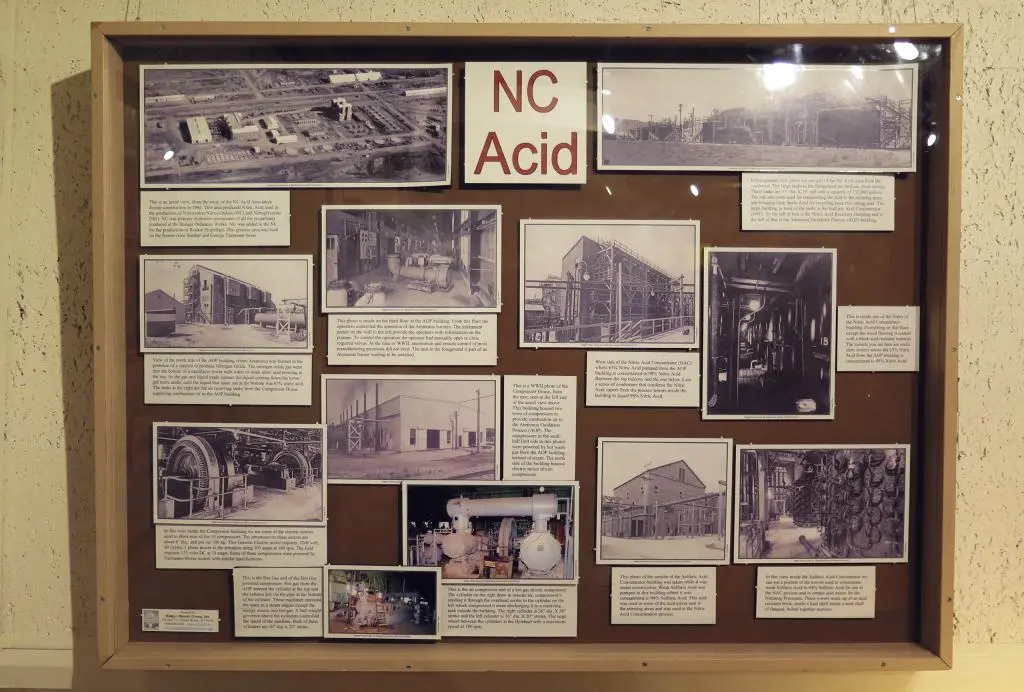

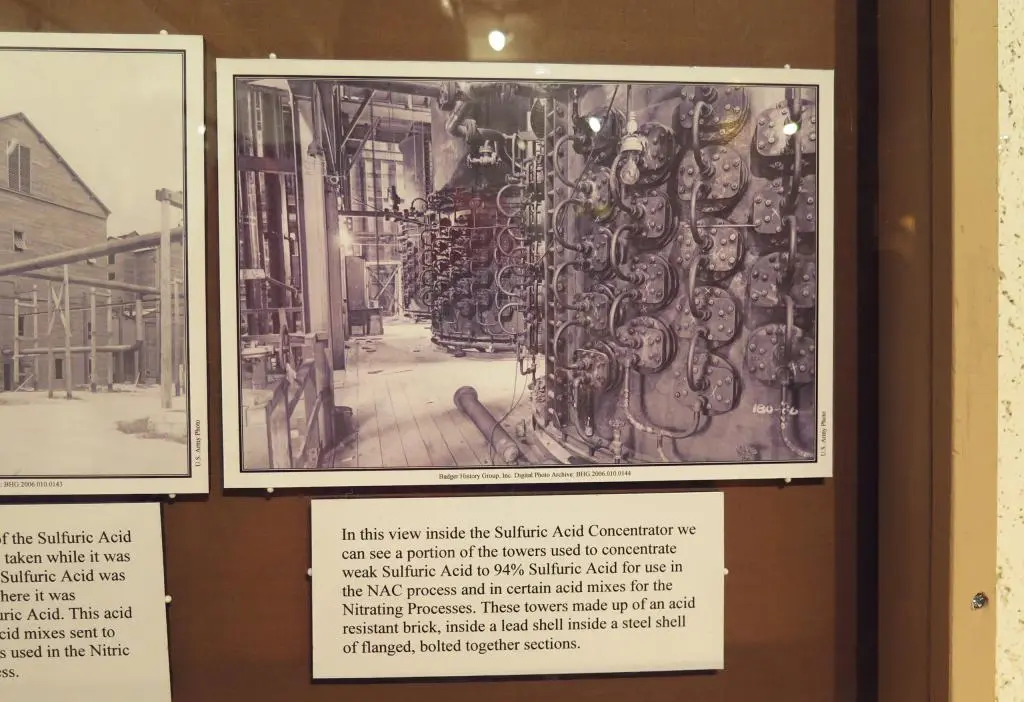

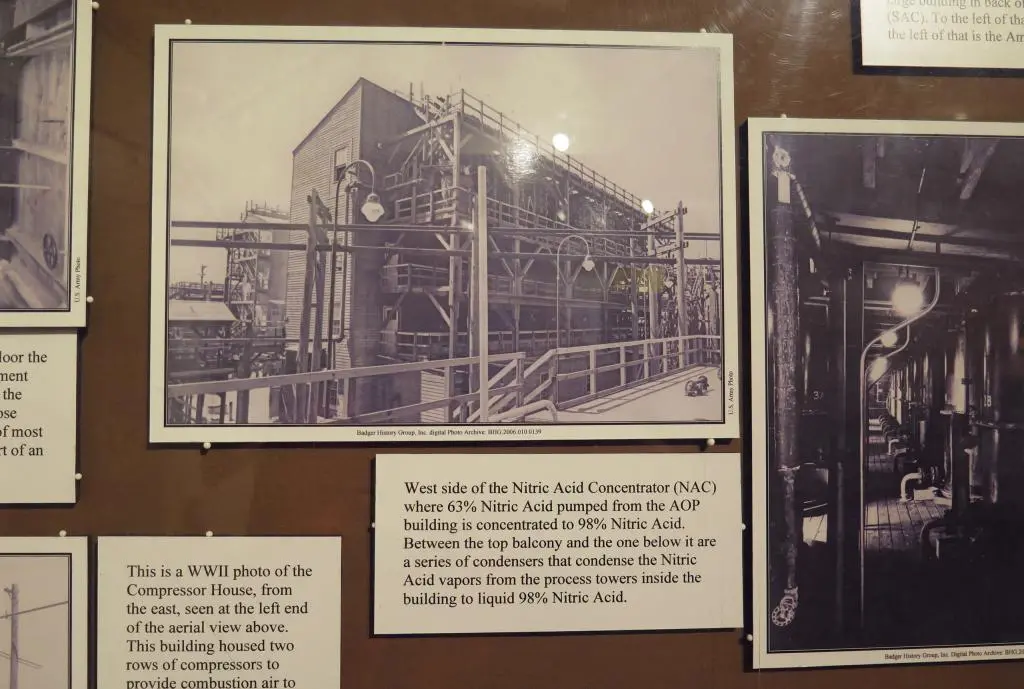

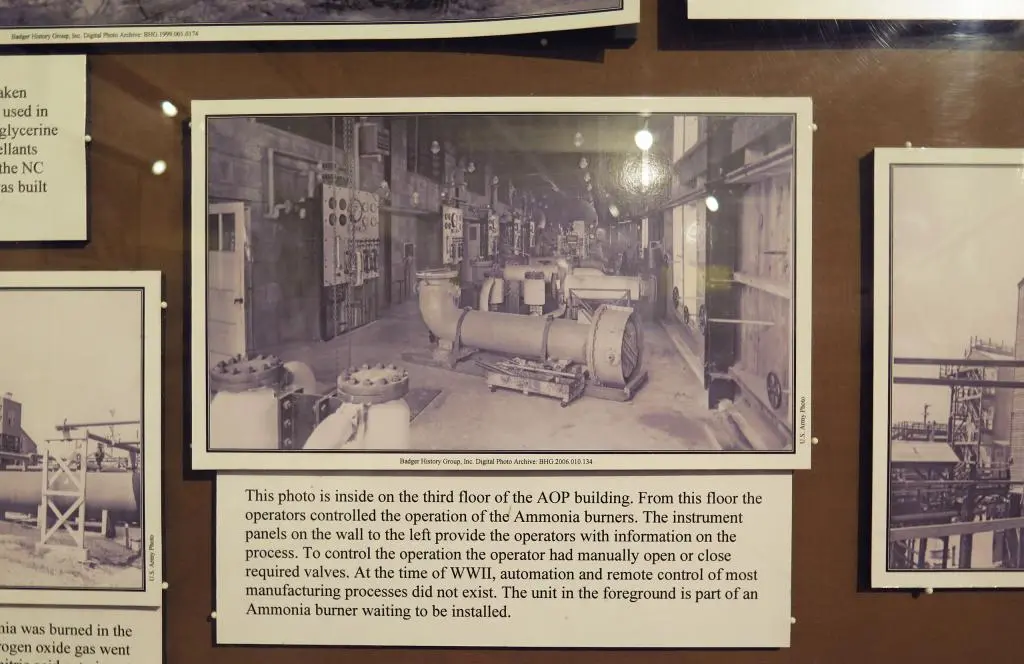

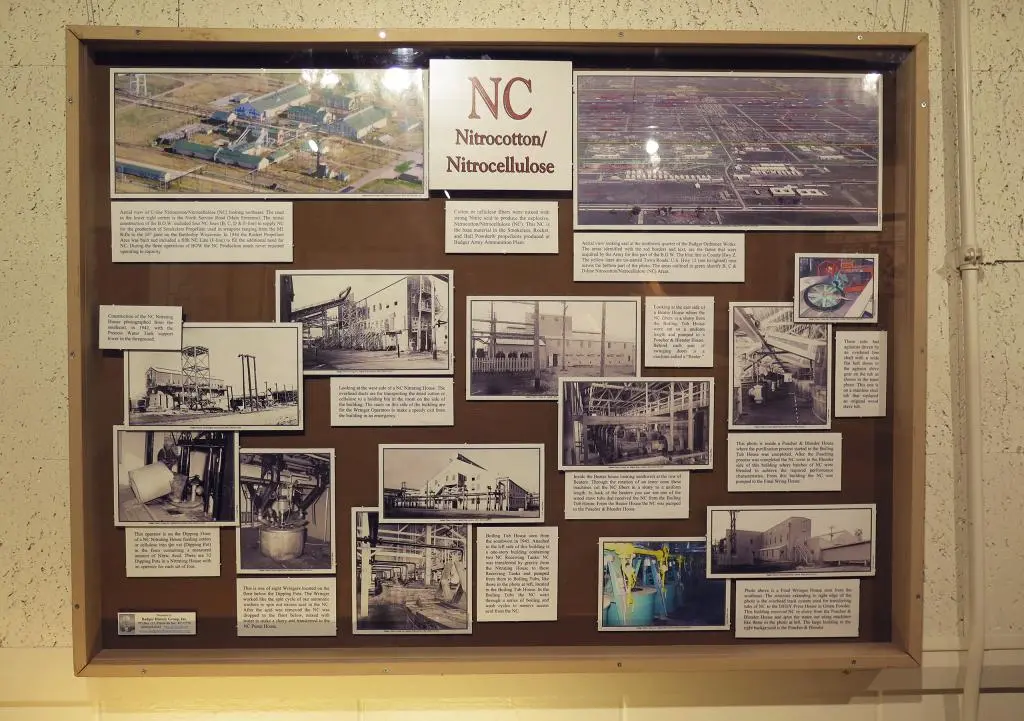

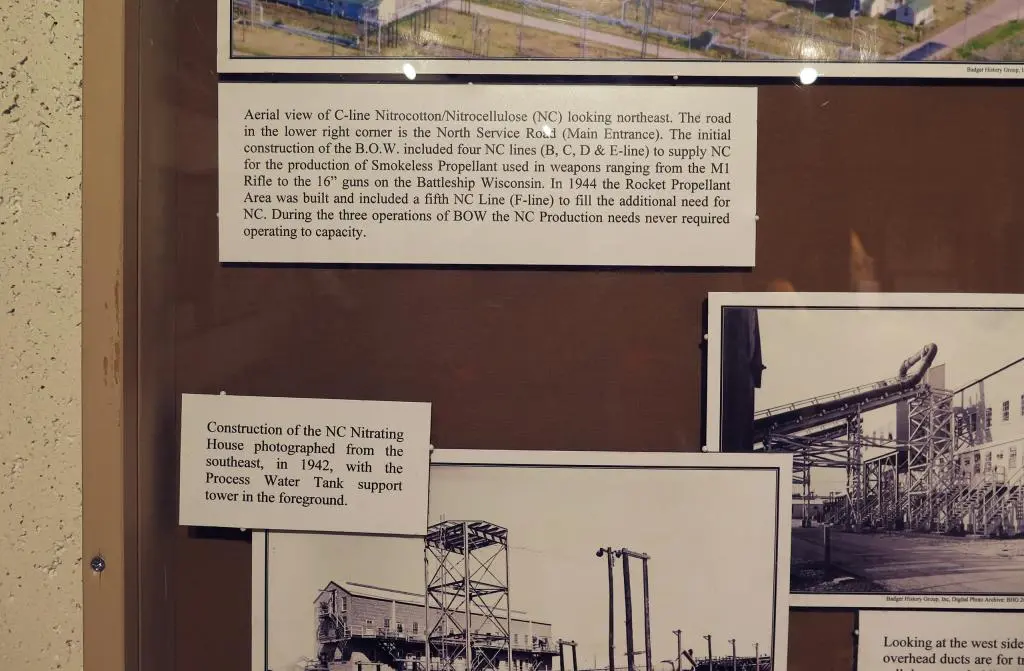

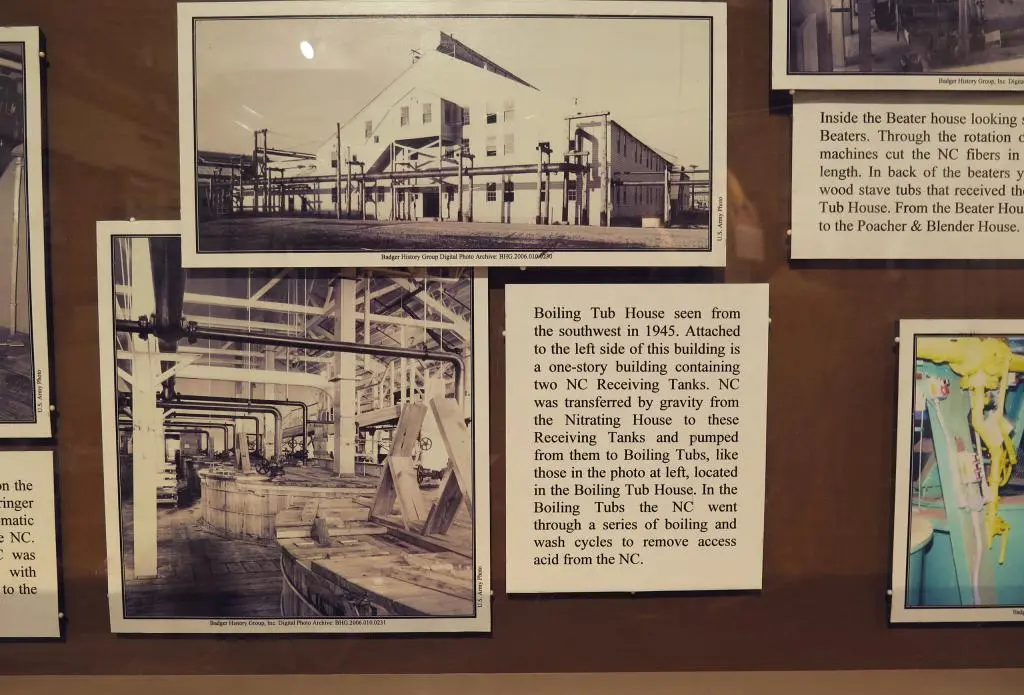

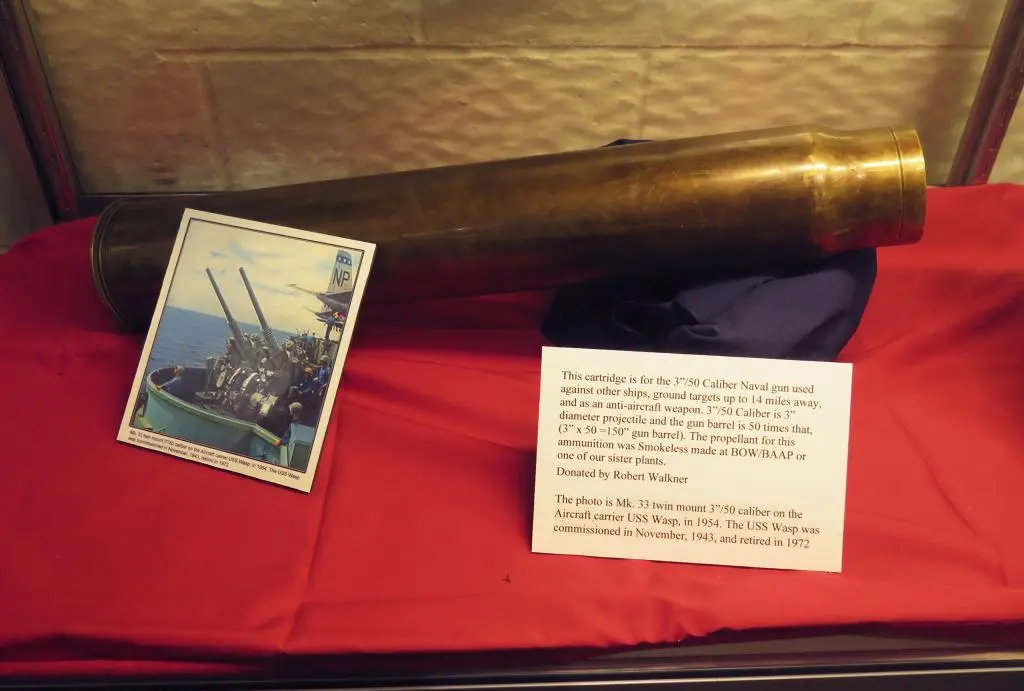

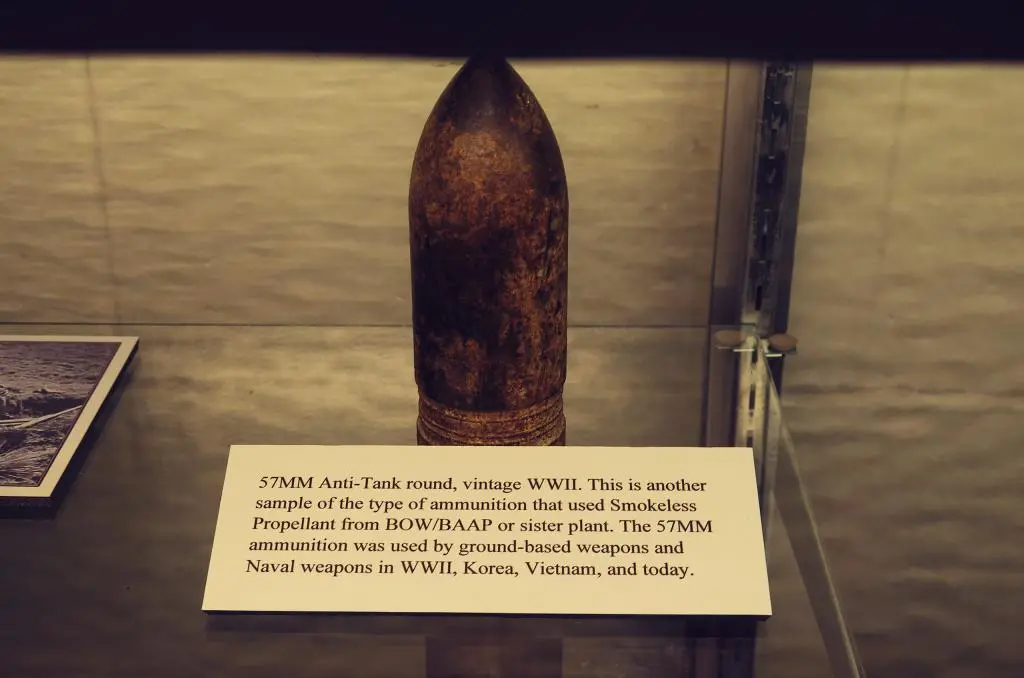

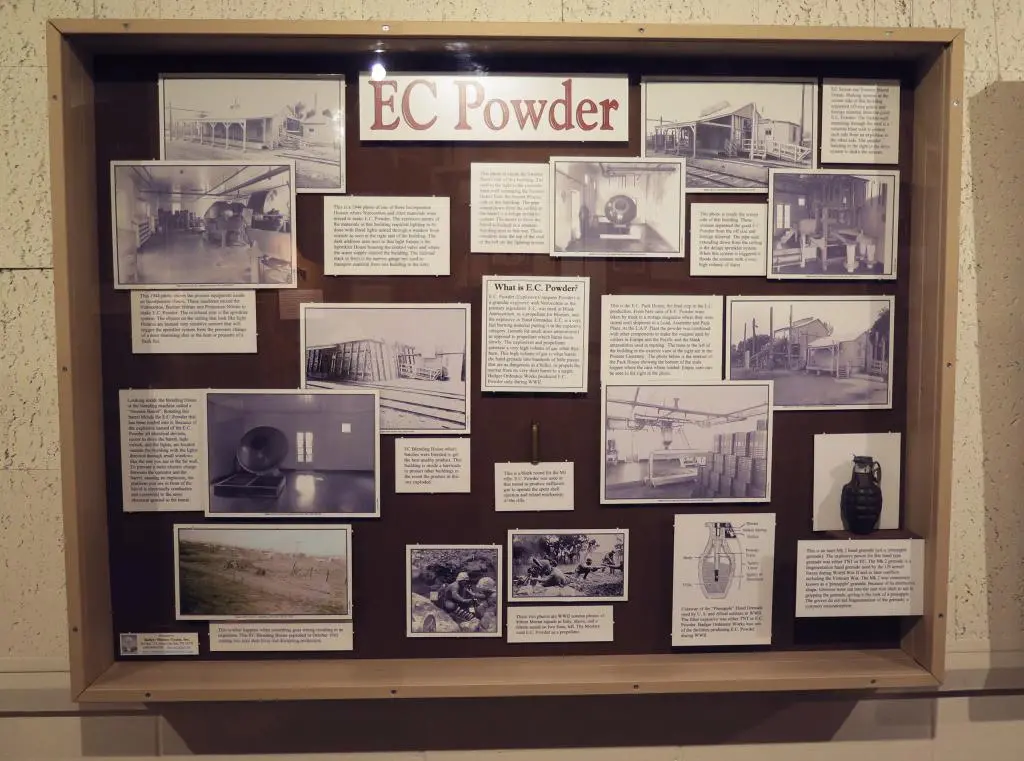

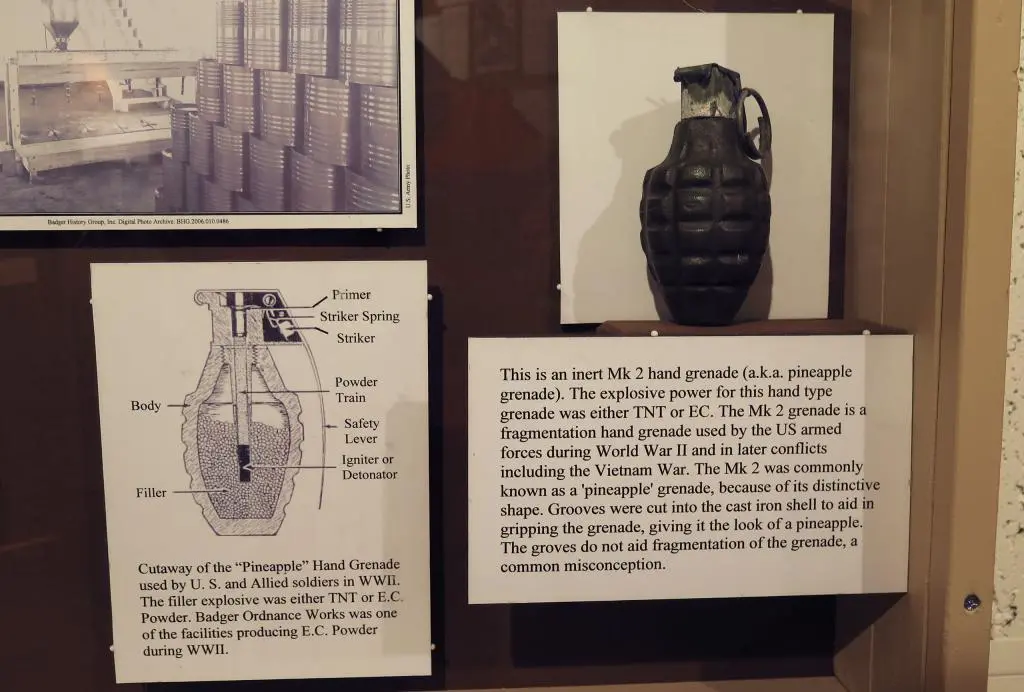

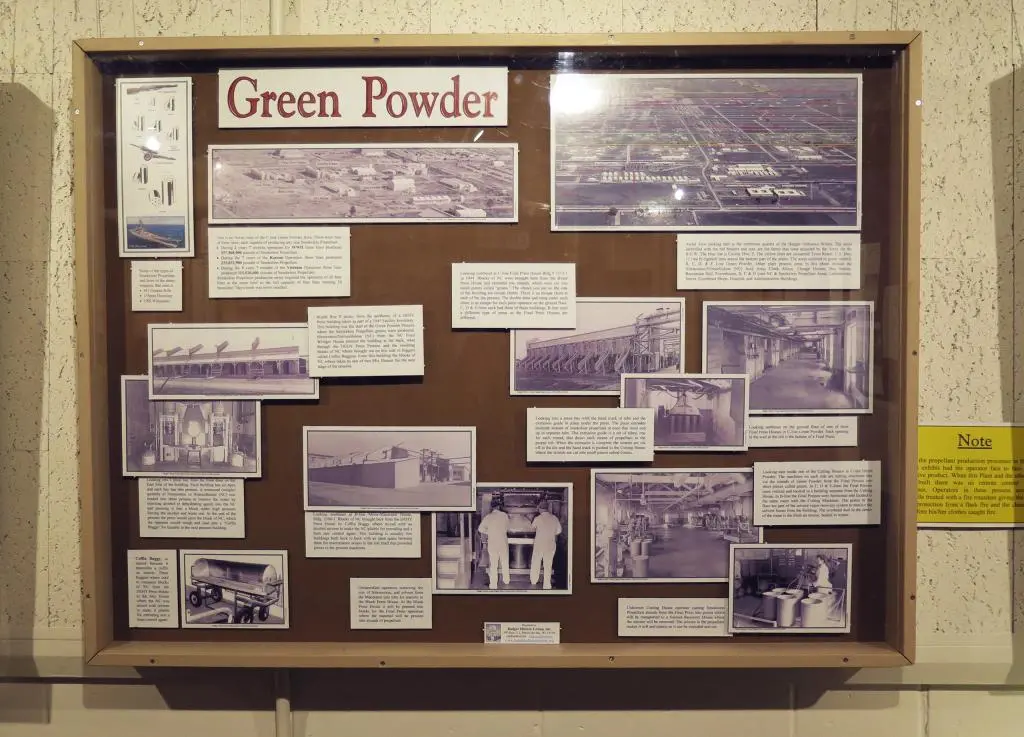

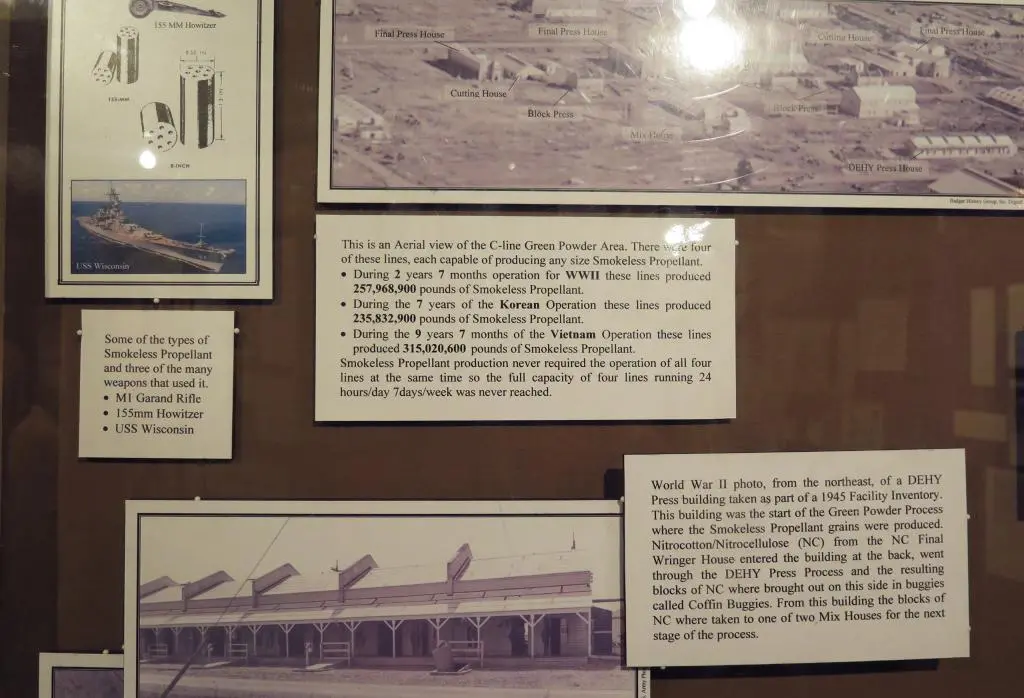

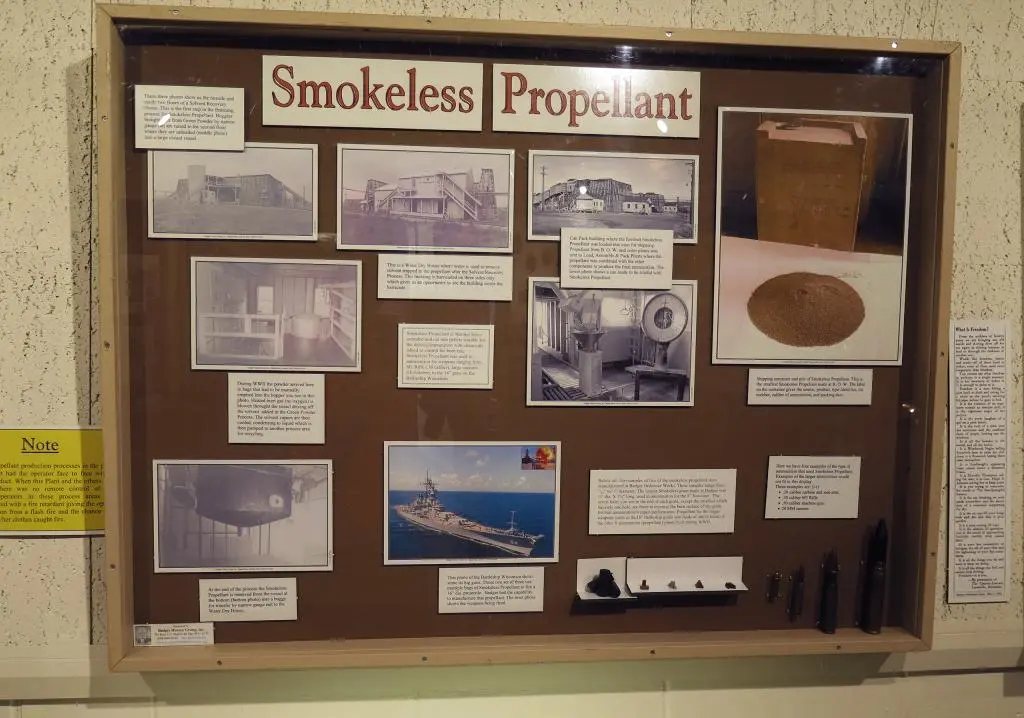

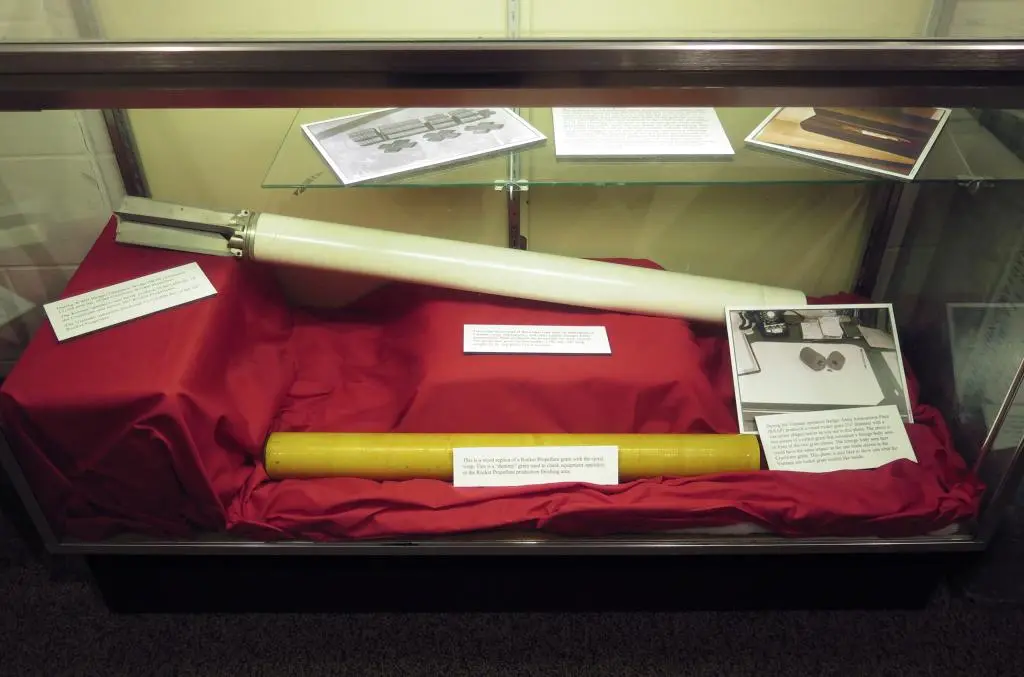

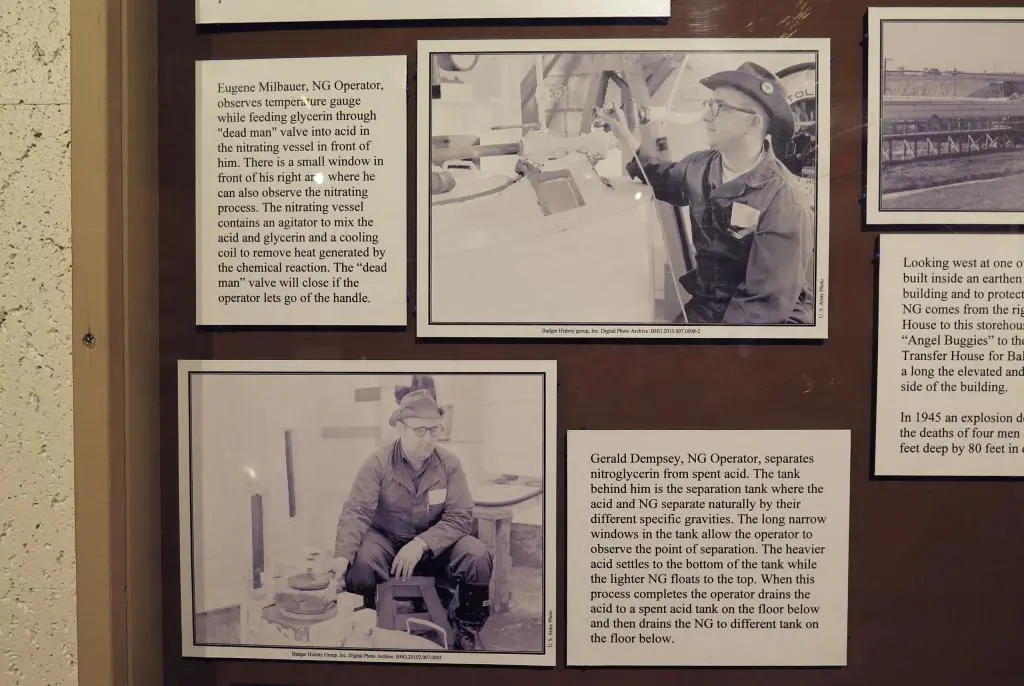

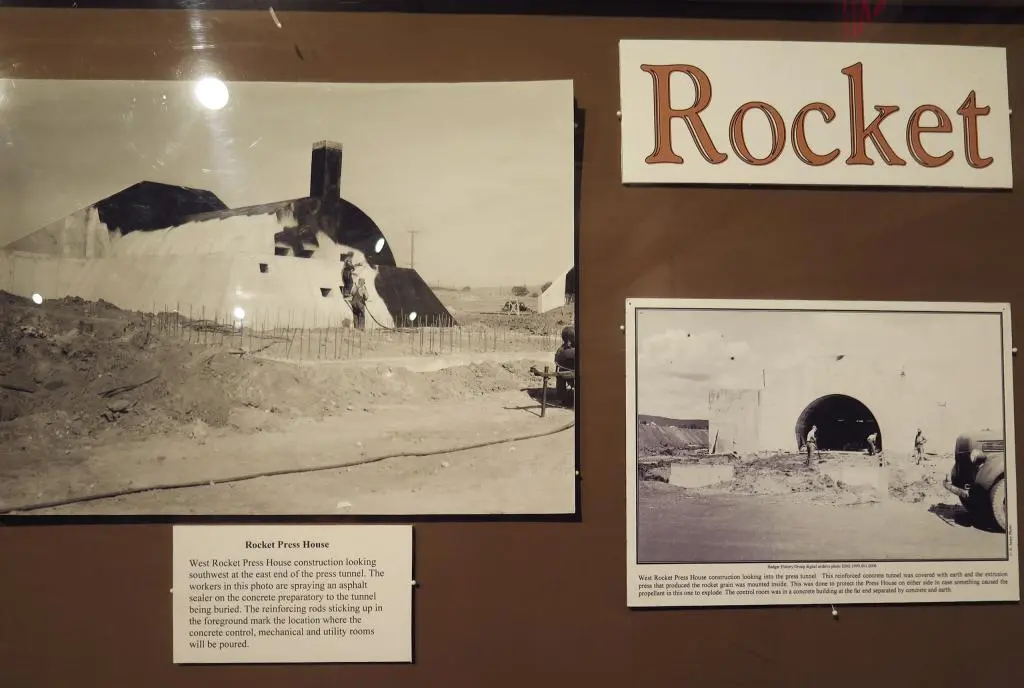

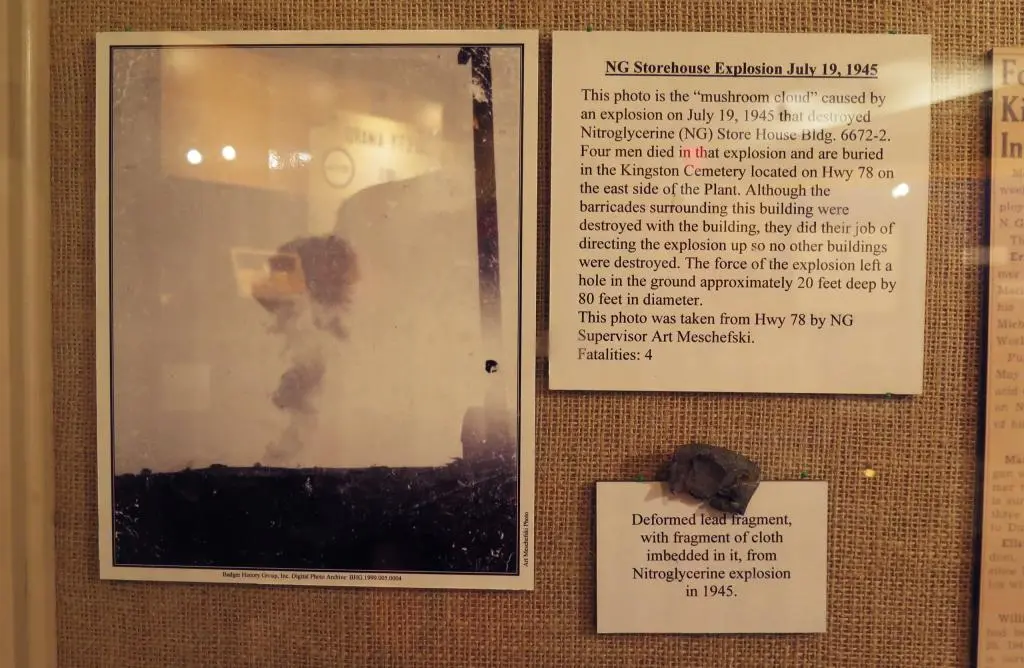

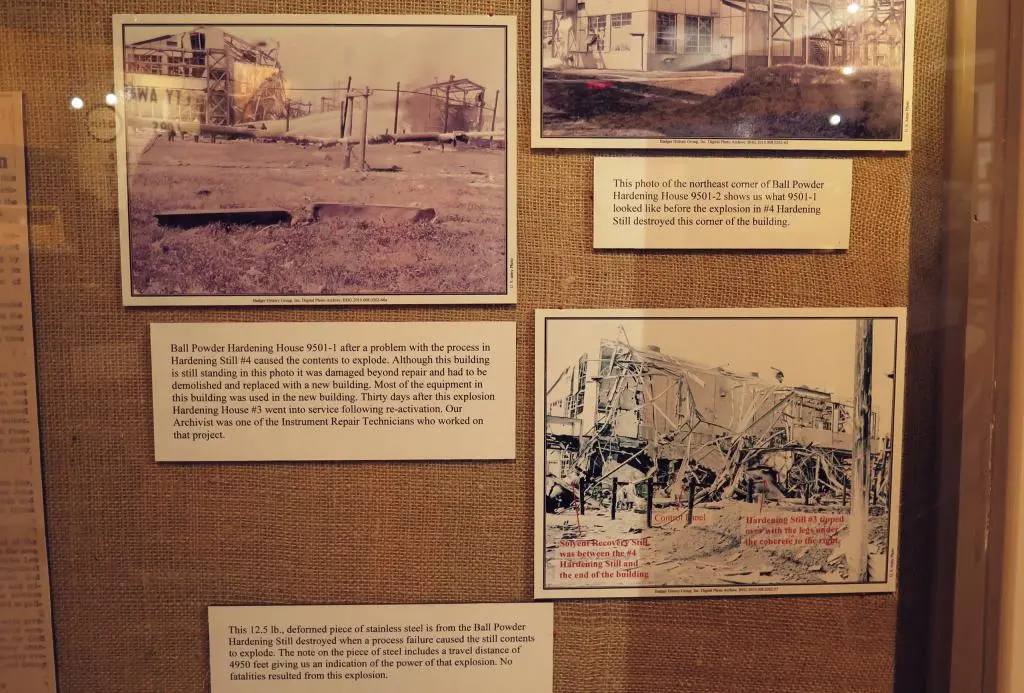

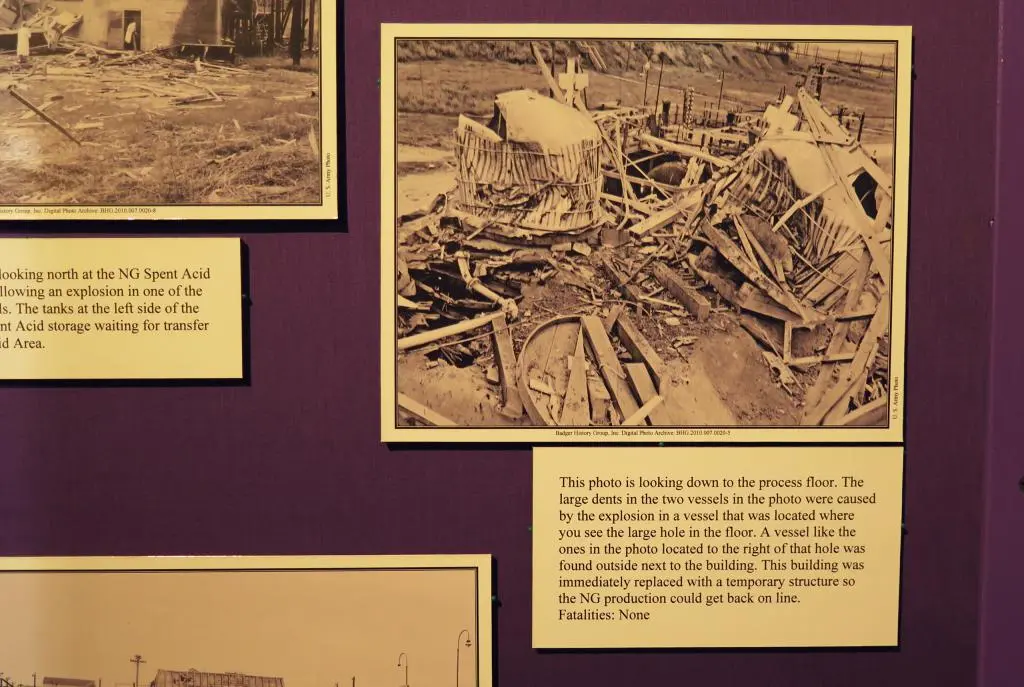

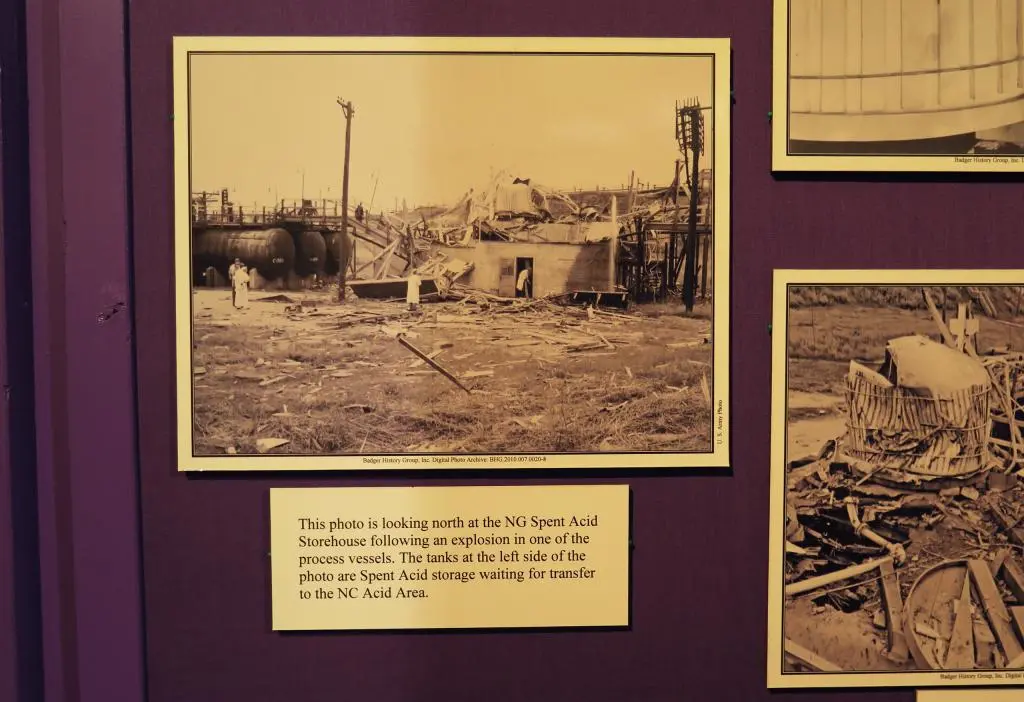

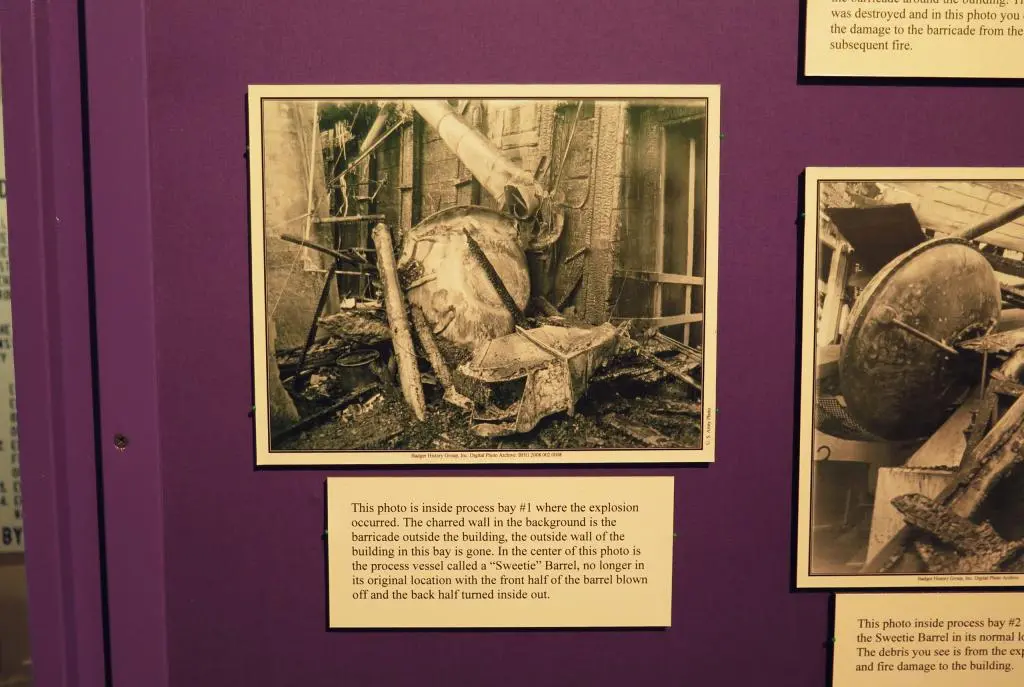

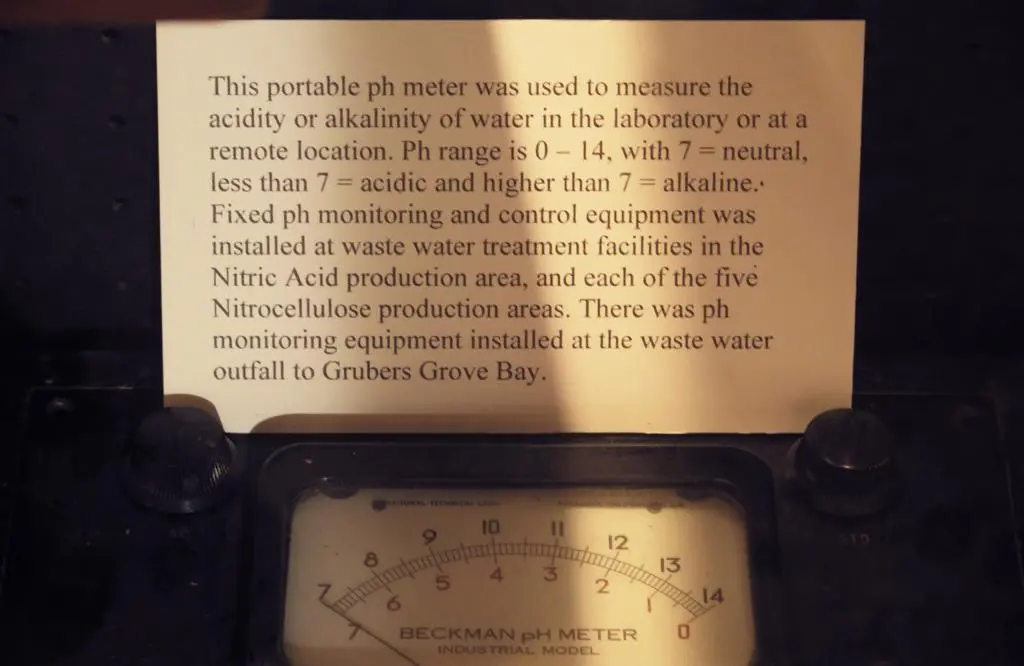

The actual full title was The Badger Army Ammunition Plant, and they did not directly manufacture bullets. Scientists and workers in the plant devleloped and synthesized Nitric Acid and Sulfric Acid combined with other agents to create rocket propellant, smokeless powder used in rifle bullets and tank shells, and explosion powder used in hand grenades and tear gas canisters.

The plant itself only developed and shipped the powder. Other plants and factors in the midwest received the powder and used them in ammunition.

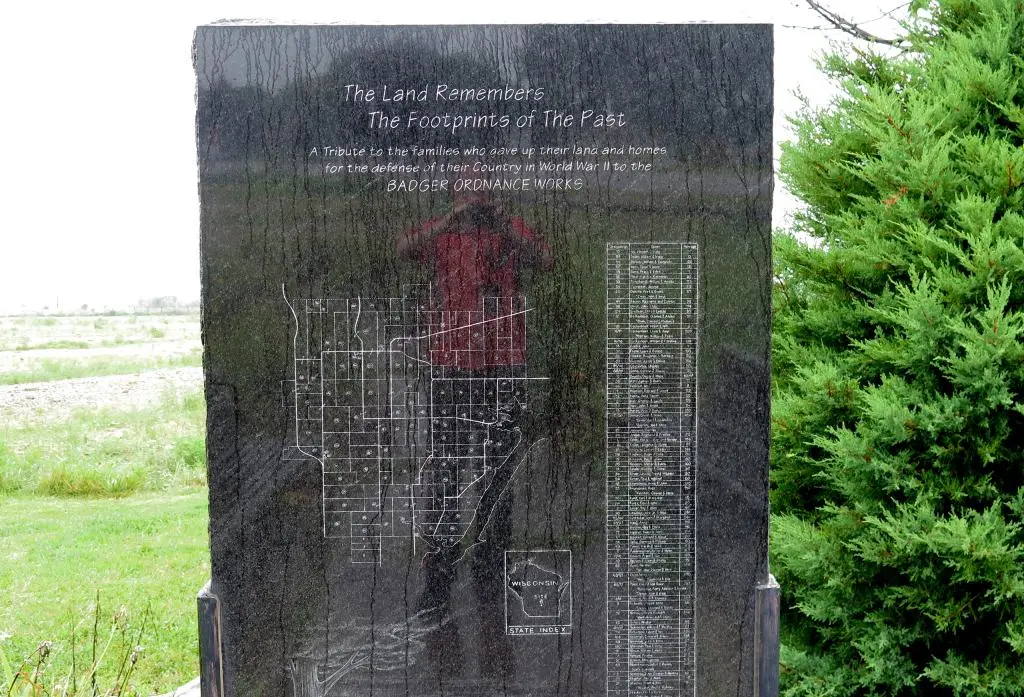

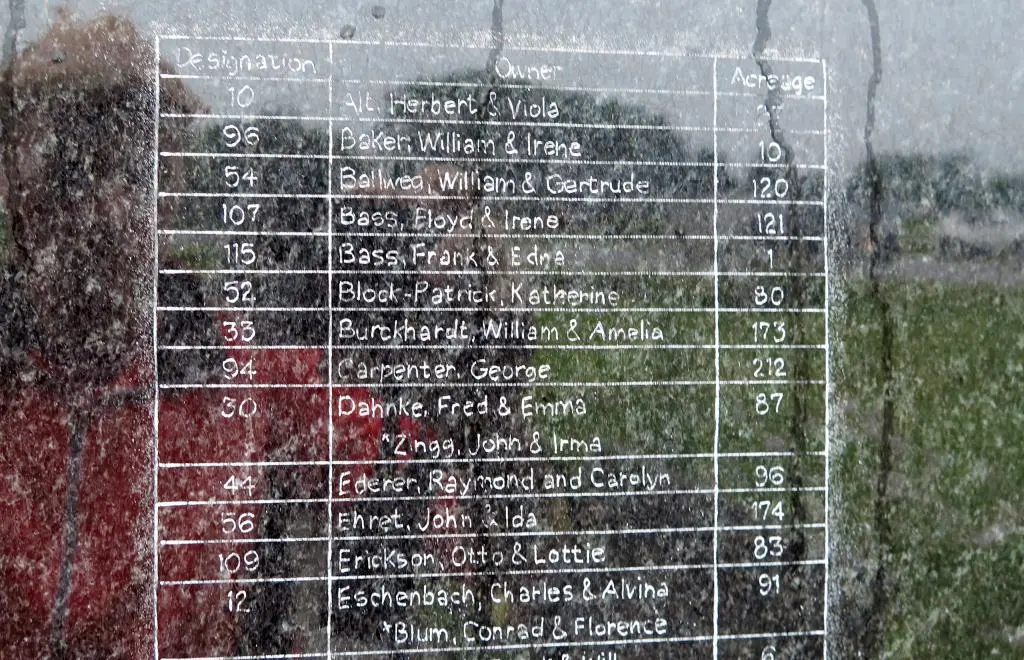

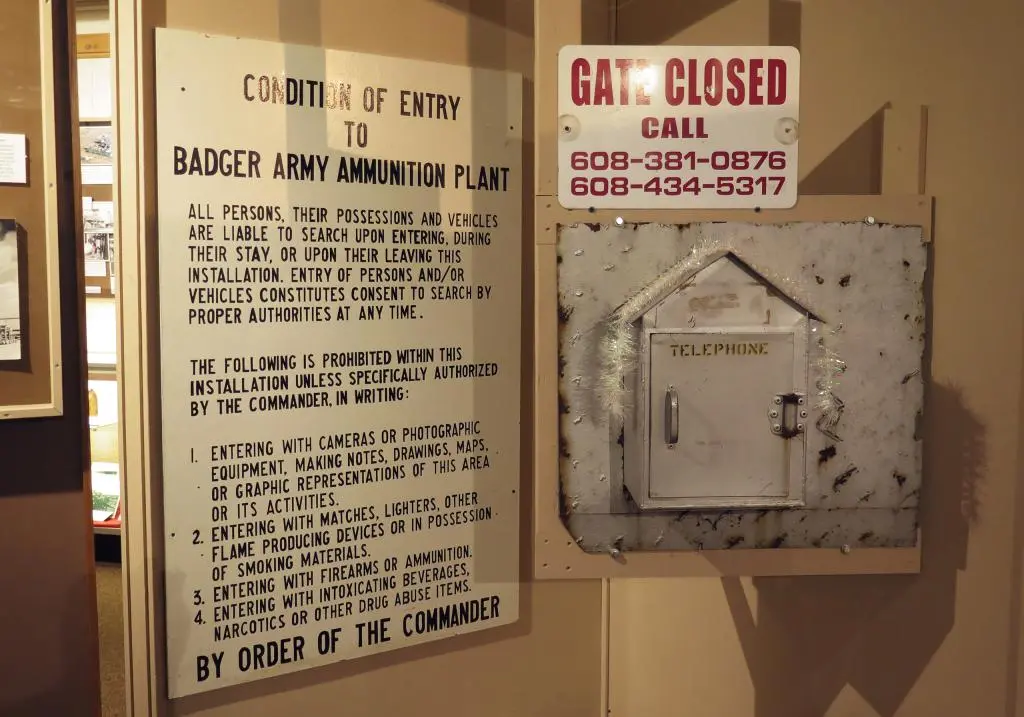

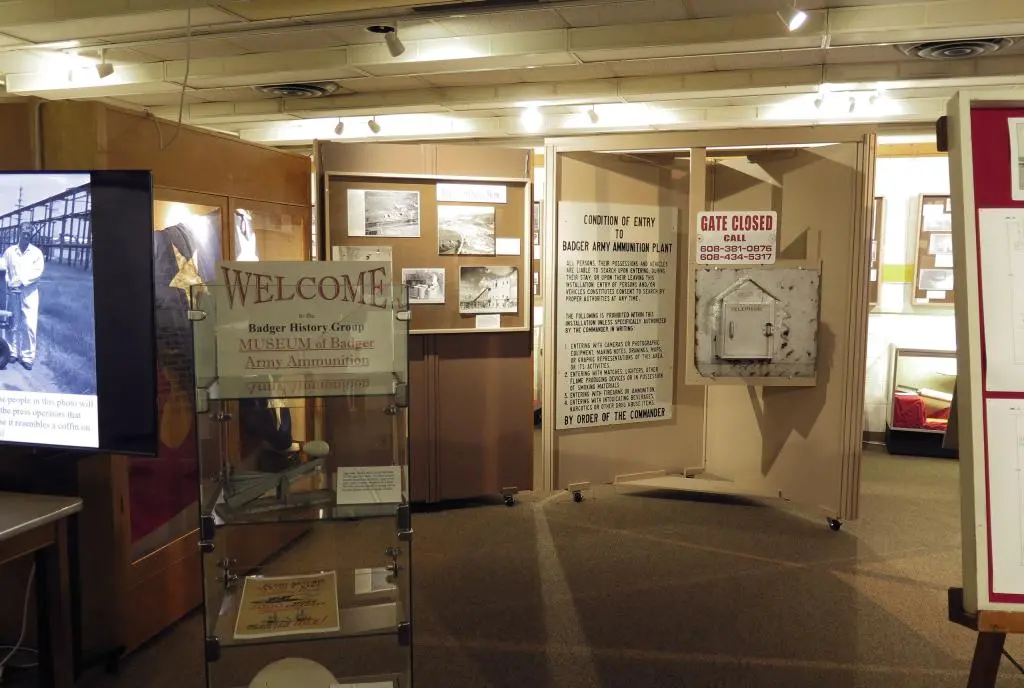

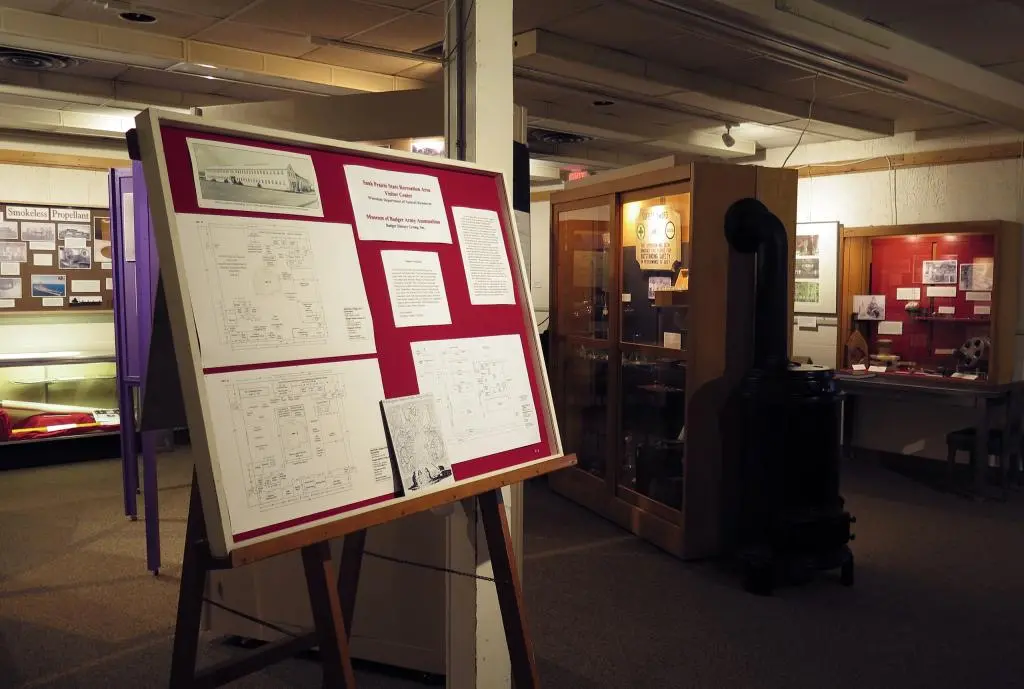

These days, there's not much to see. Full demolition of all buildings was completed in 2013. The security gate entrance was still standing, and seemed like the only remaining original building in the lot. Outside of the entrance, to the left, was a memorial stone showing the families that "gave up" their land for the plant to be built. To the right was a modern building that served as the museum to the plant and a headquarters for the Badger History Group.

The grounds inside the fence were open to explore, but there were many No Trespassing signs indicating that lands were owned by the Ho-Chunk Nation. Later, I noticed that not all of the lands were in possession of the Ho-Chunk, and it was okay to drive around most of the area.

I did drive around the area anyways and found a pair of storage shelters. Looking online through old photos, these appear to be a few more original buildings. These days, some local farmers were using them to store hay bails.

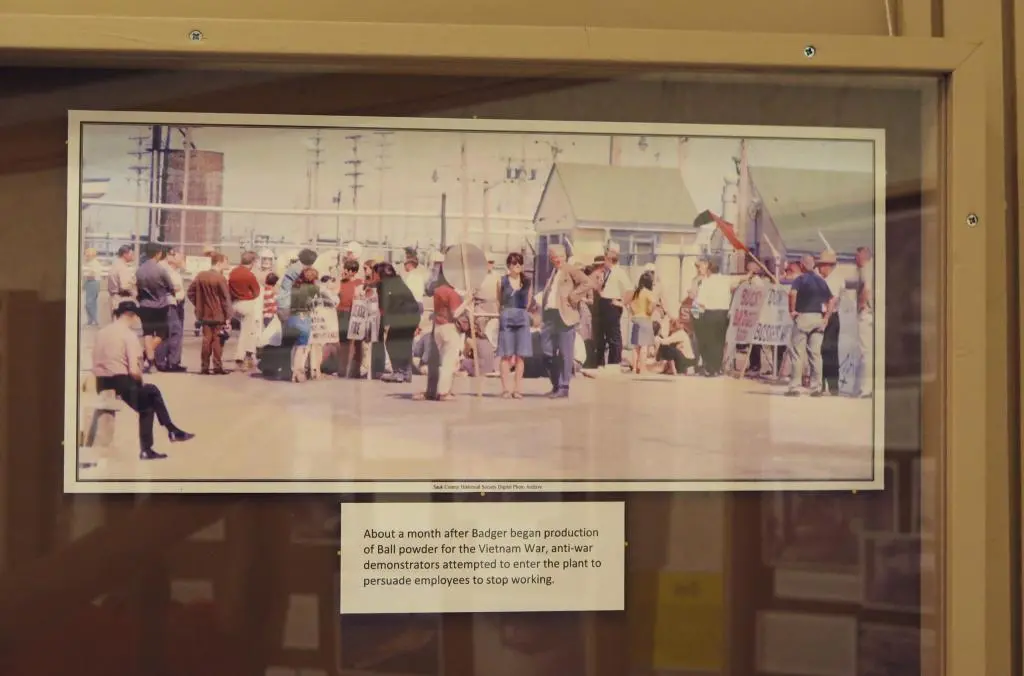

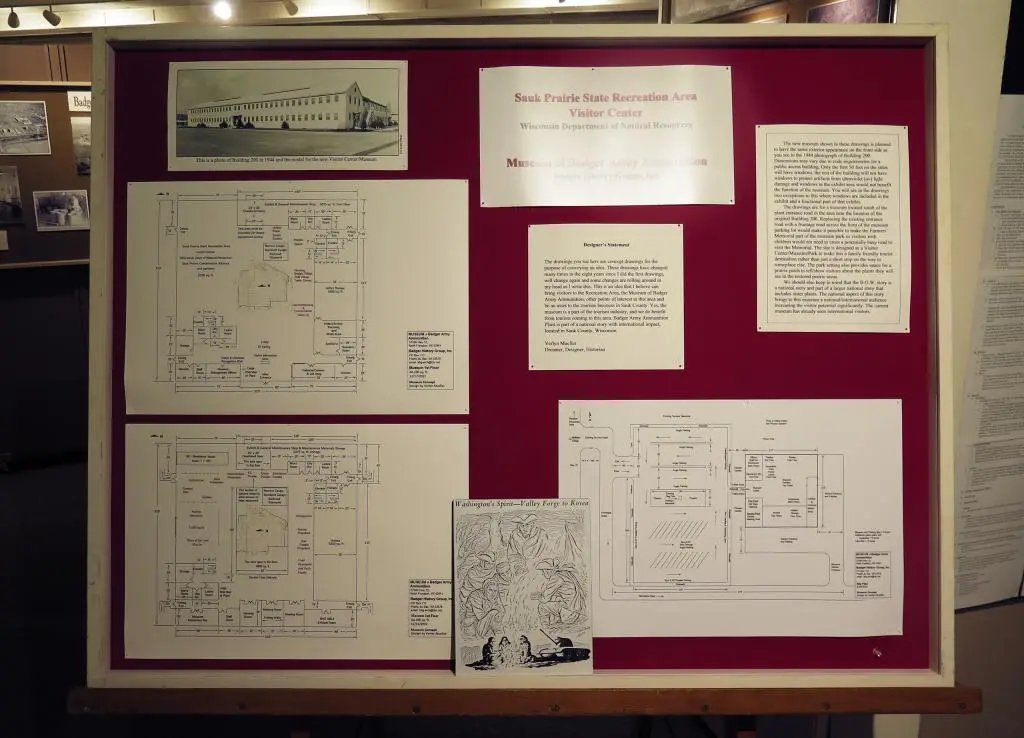

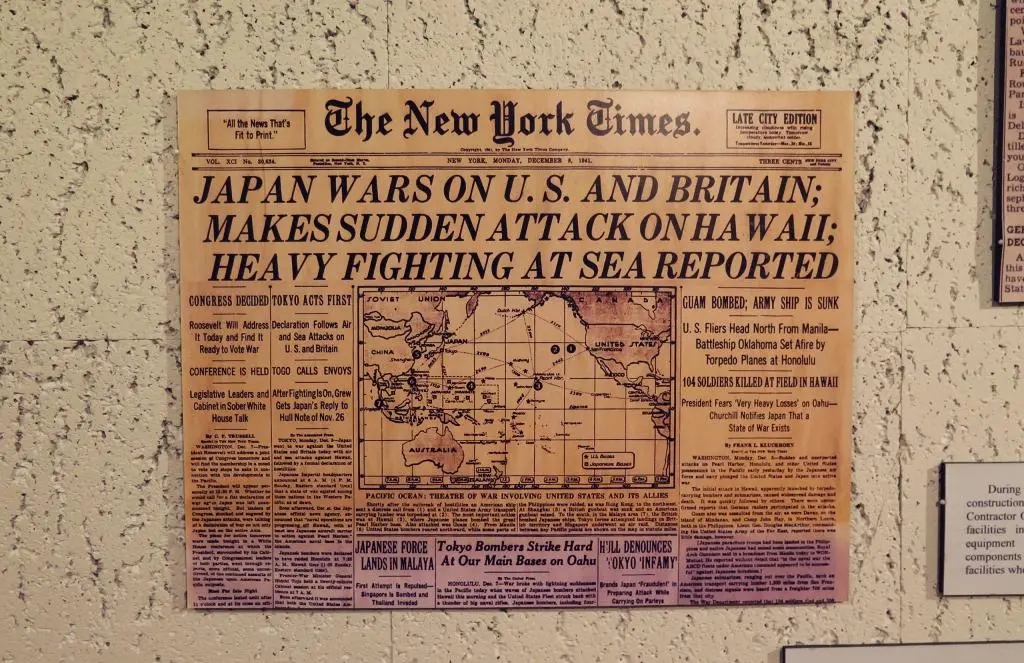

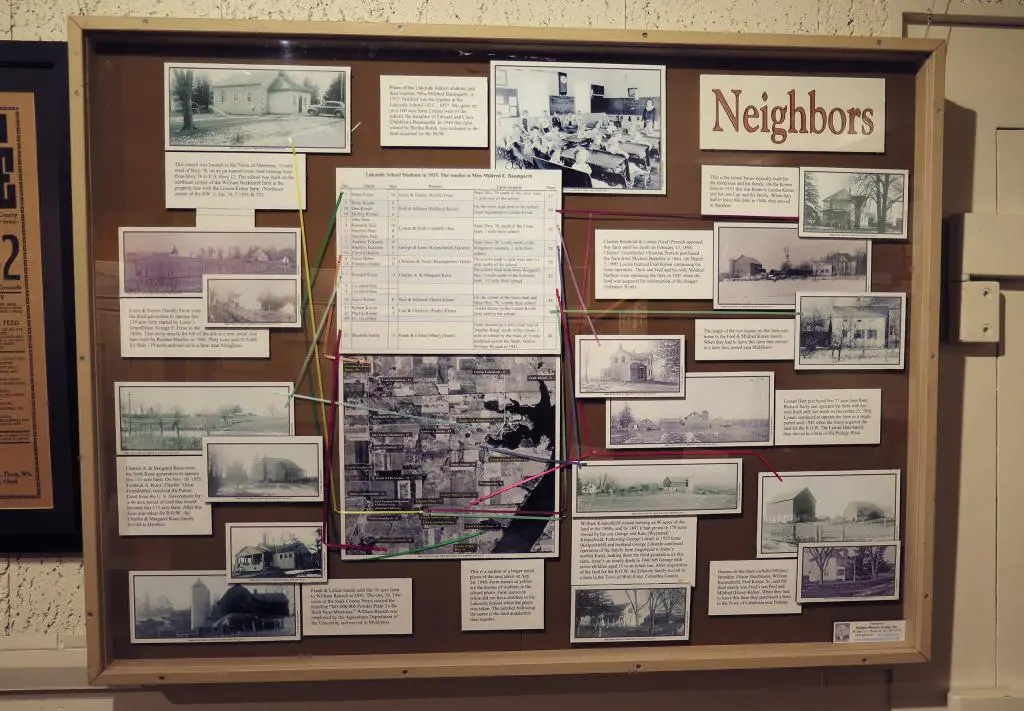

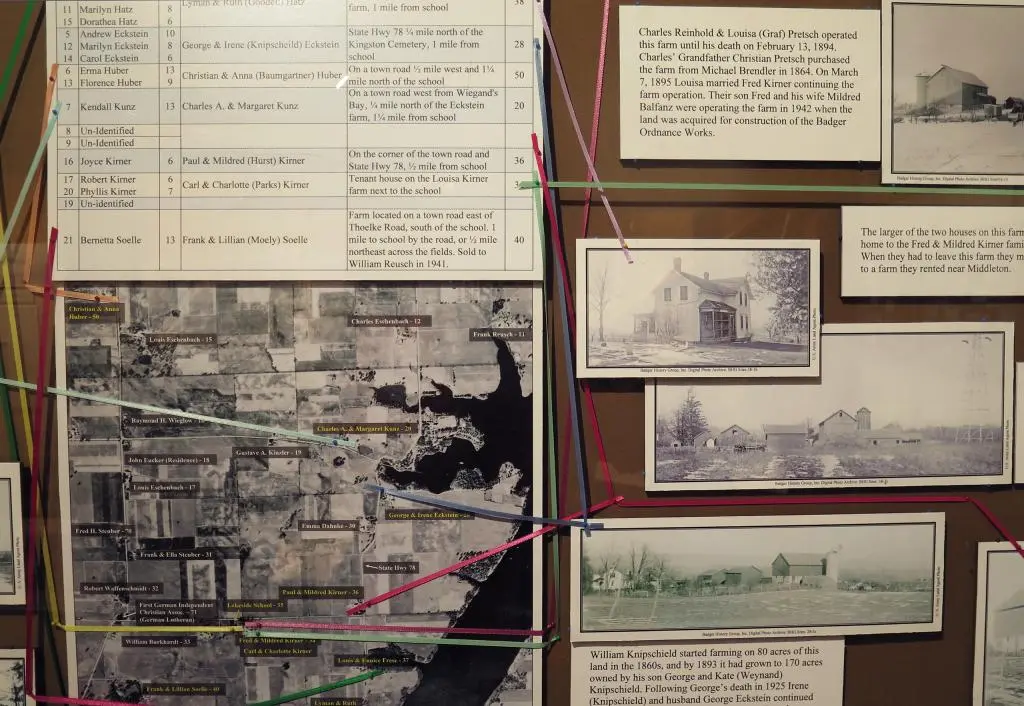

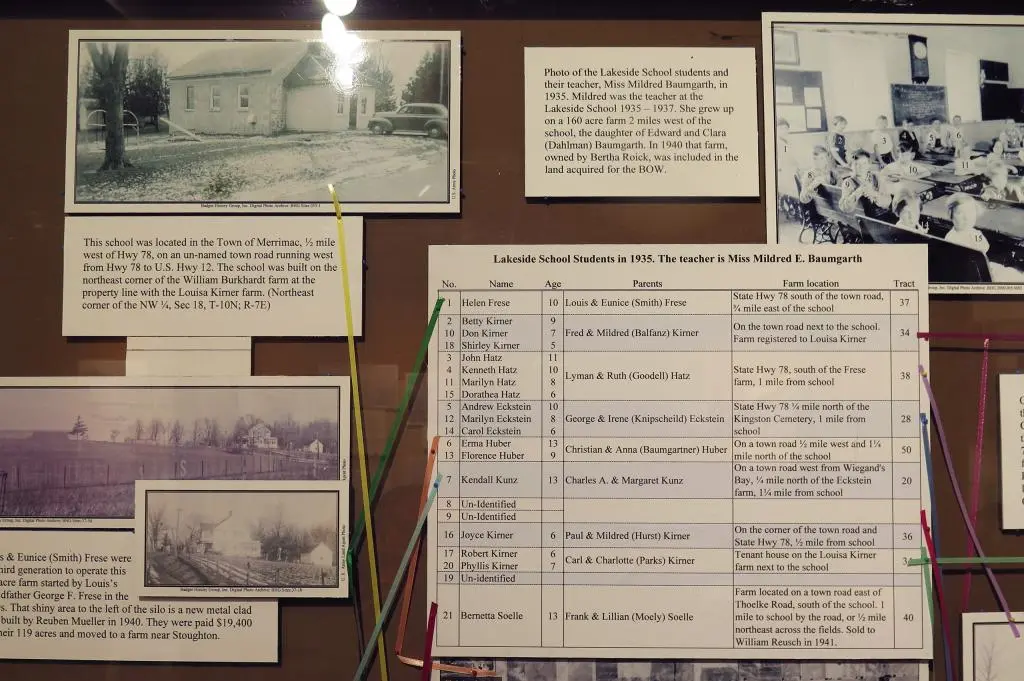

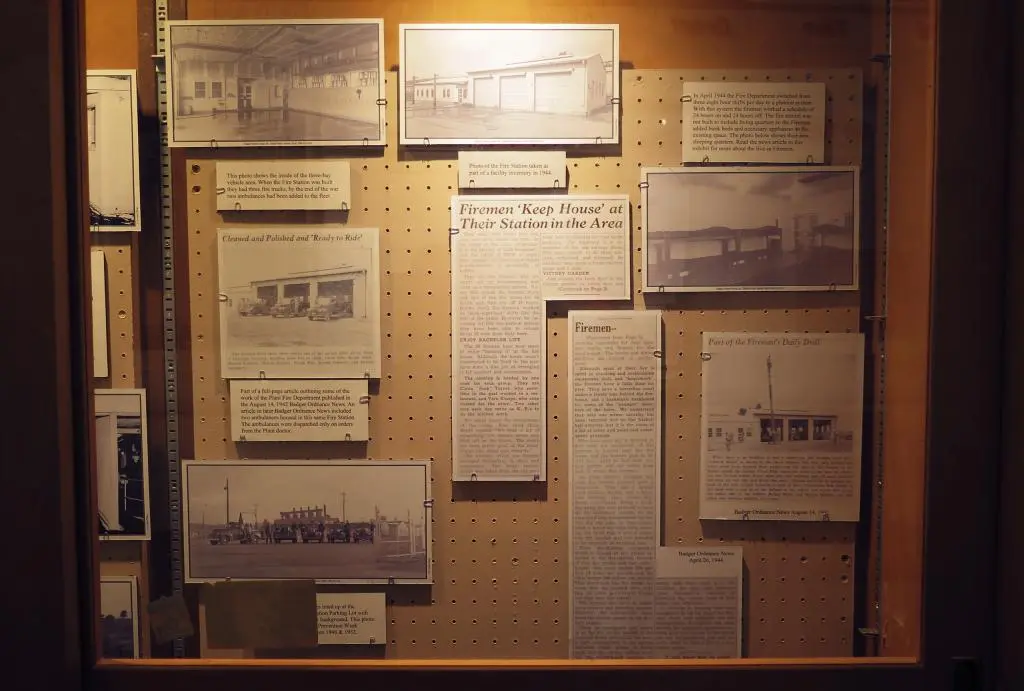

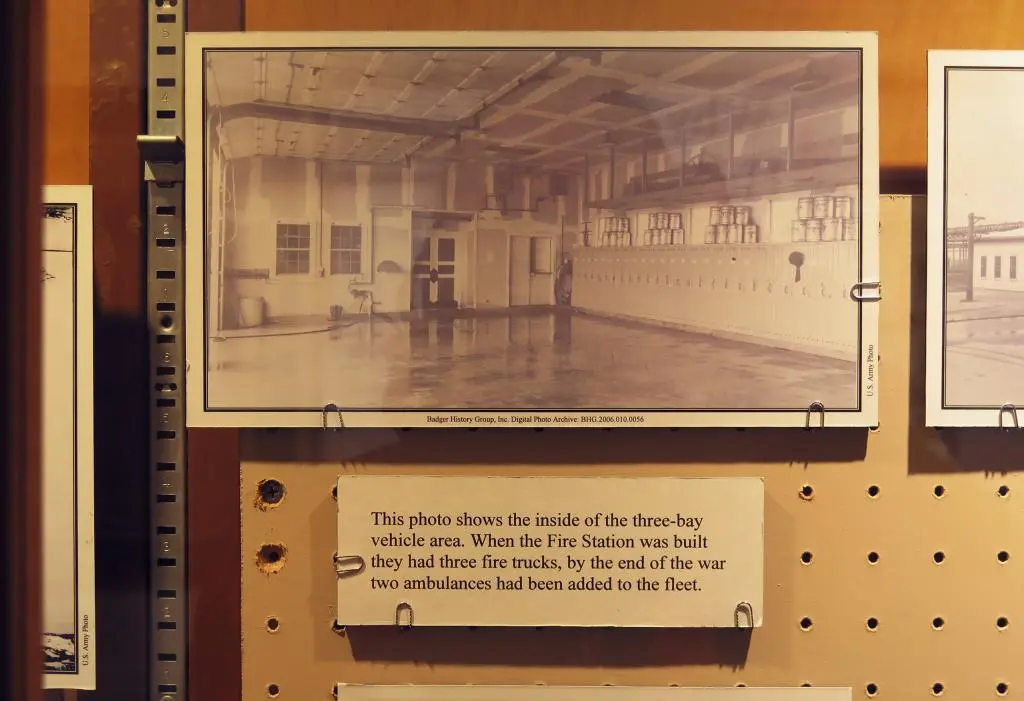

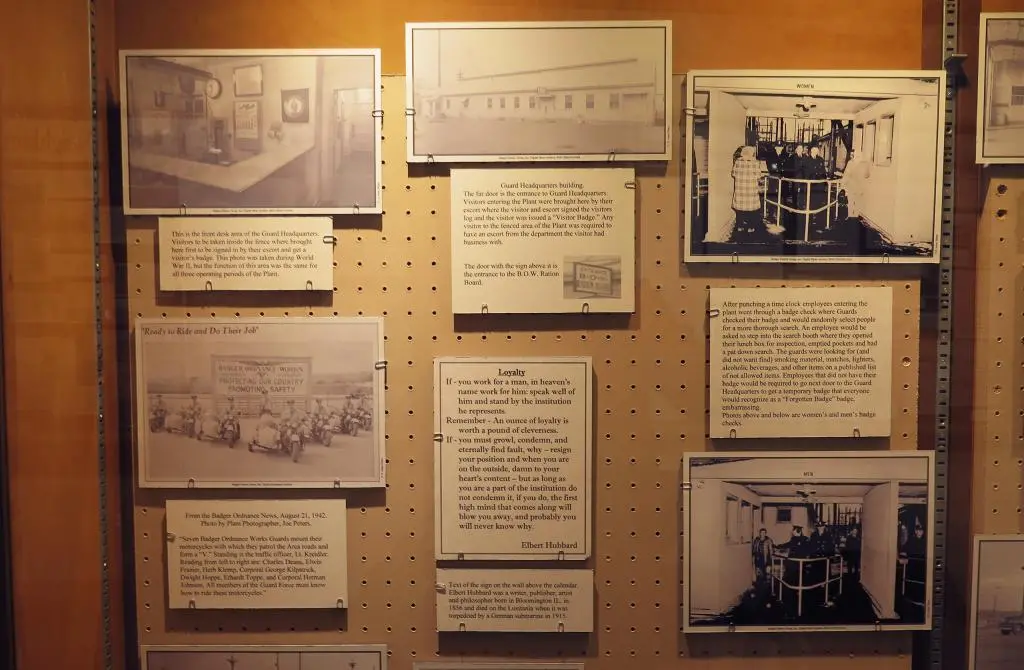

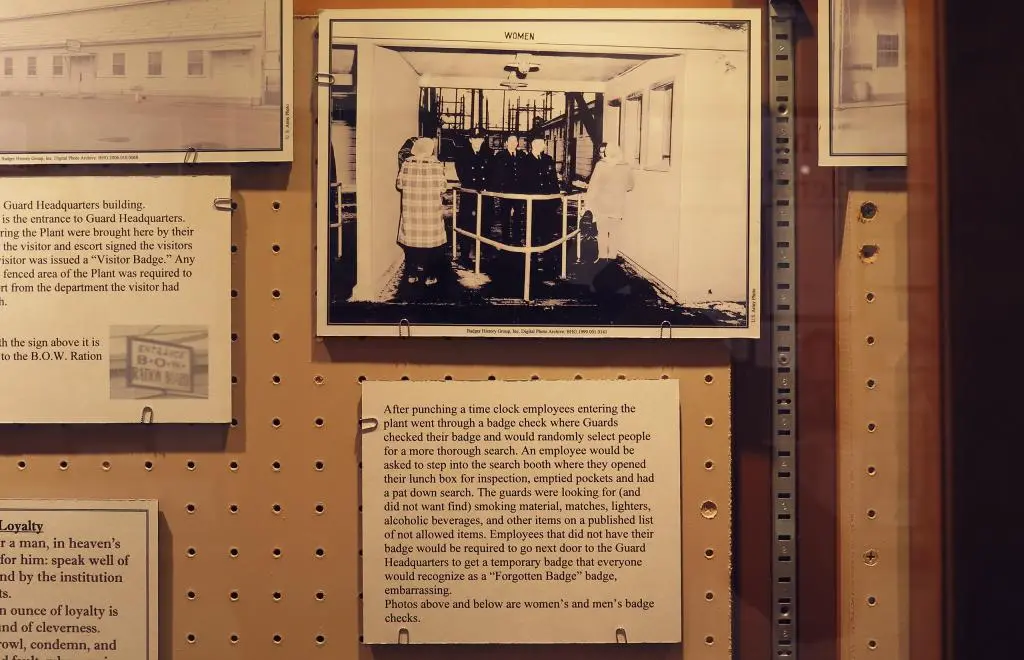

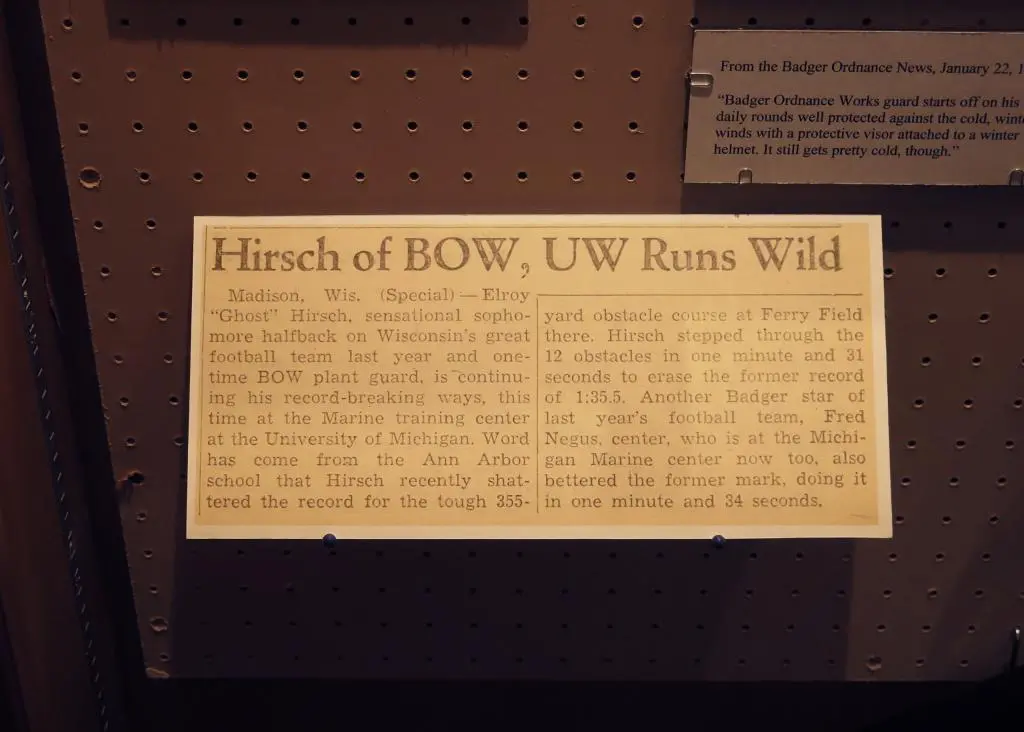

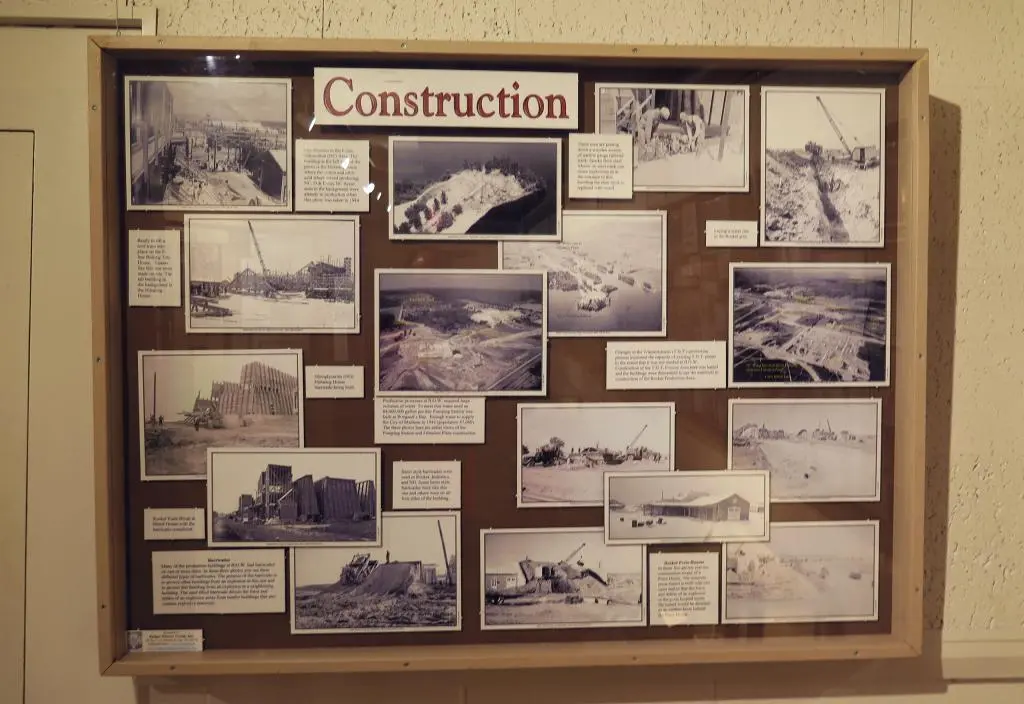

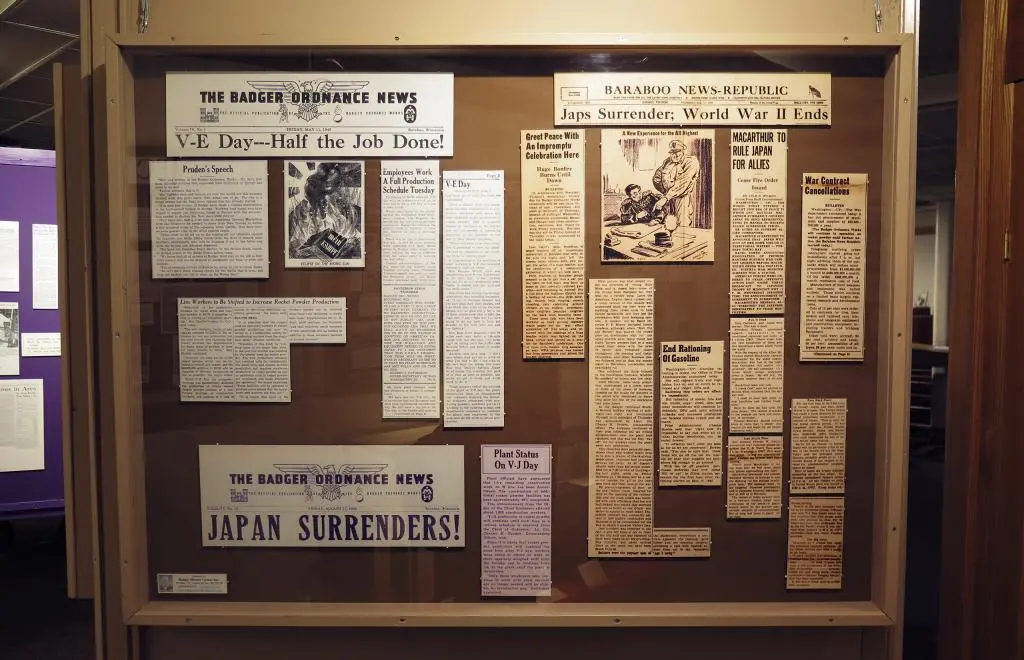

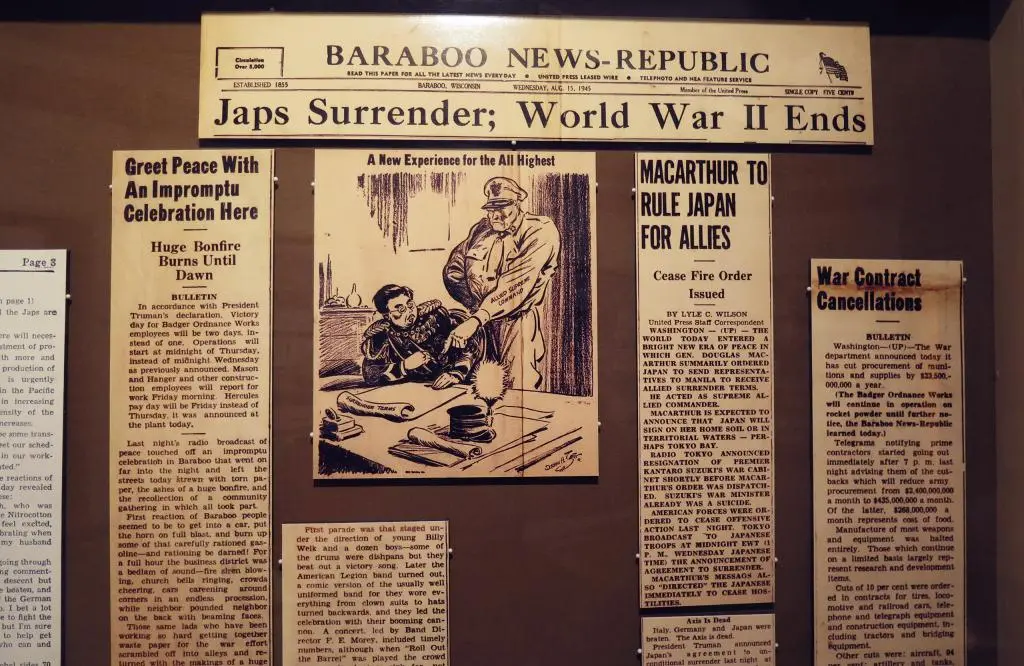

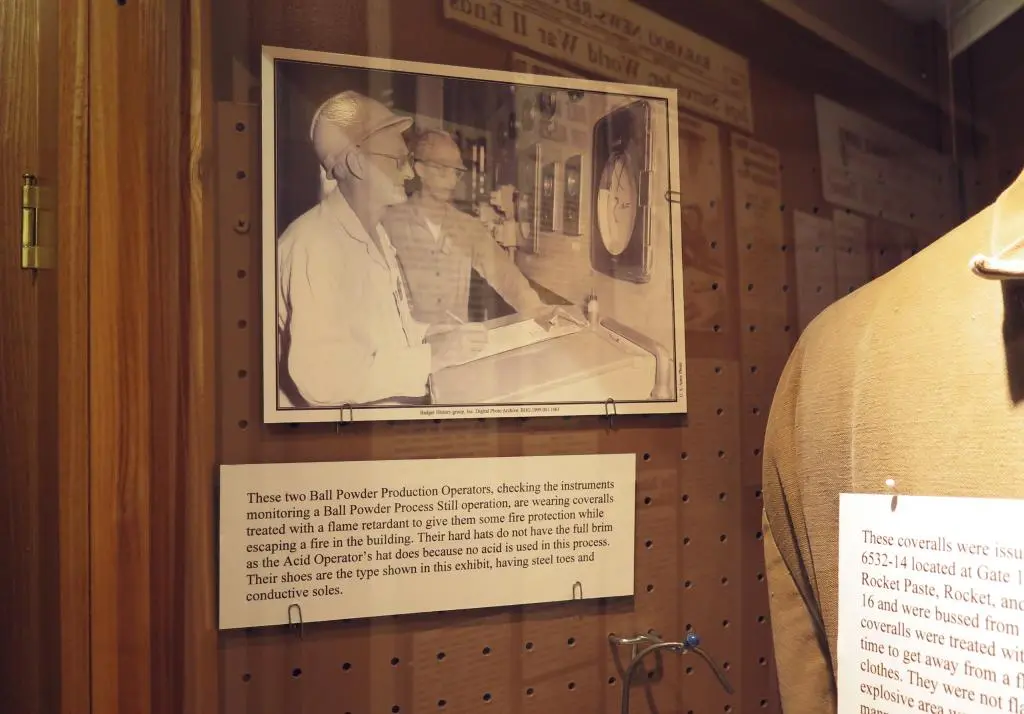

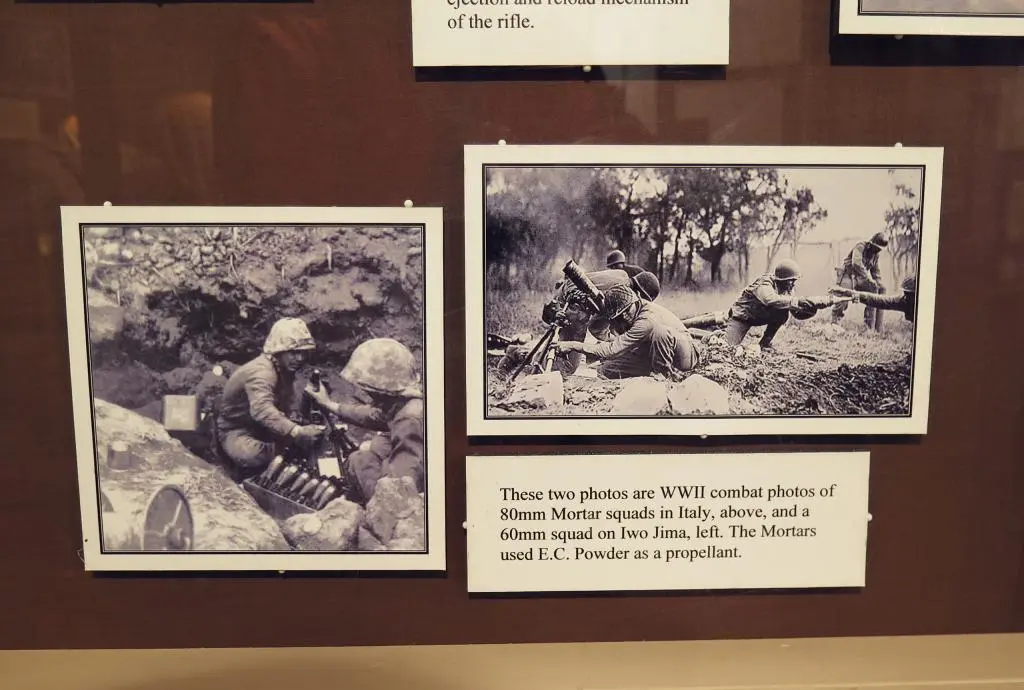

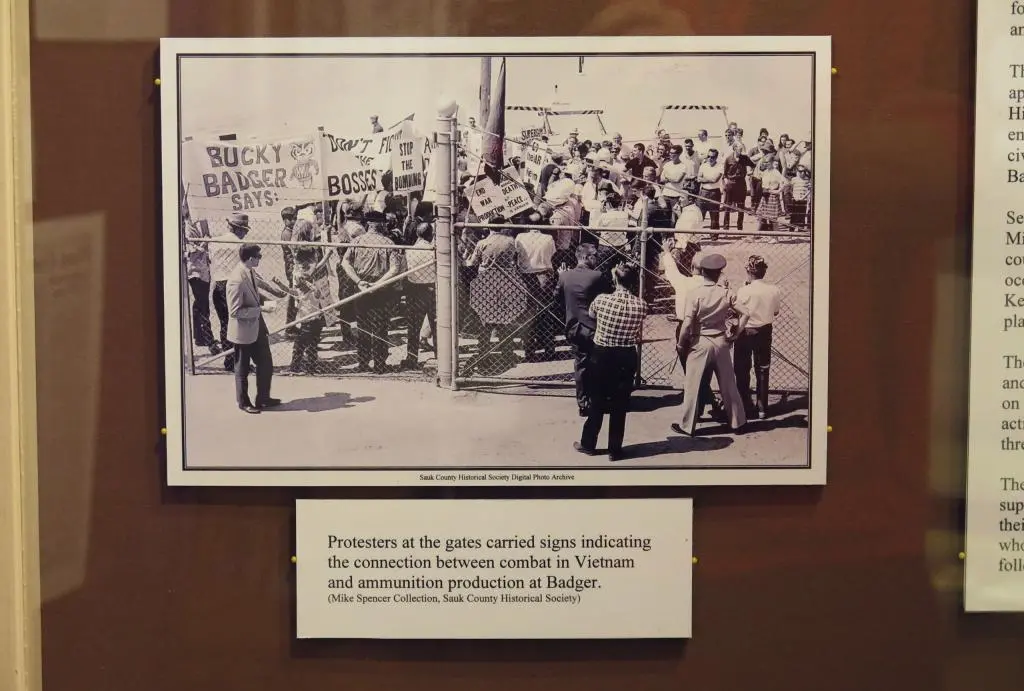

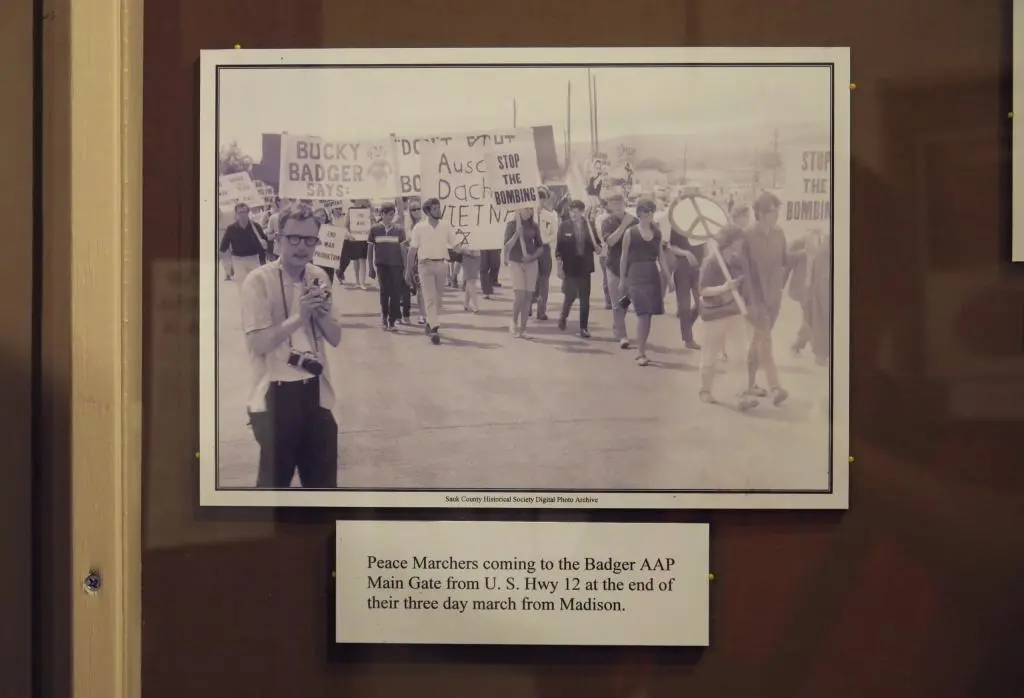

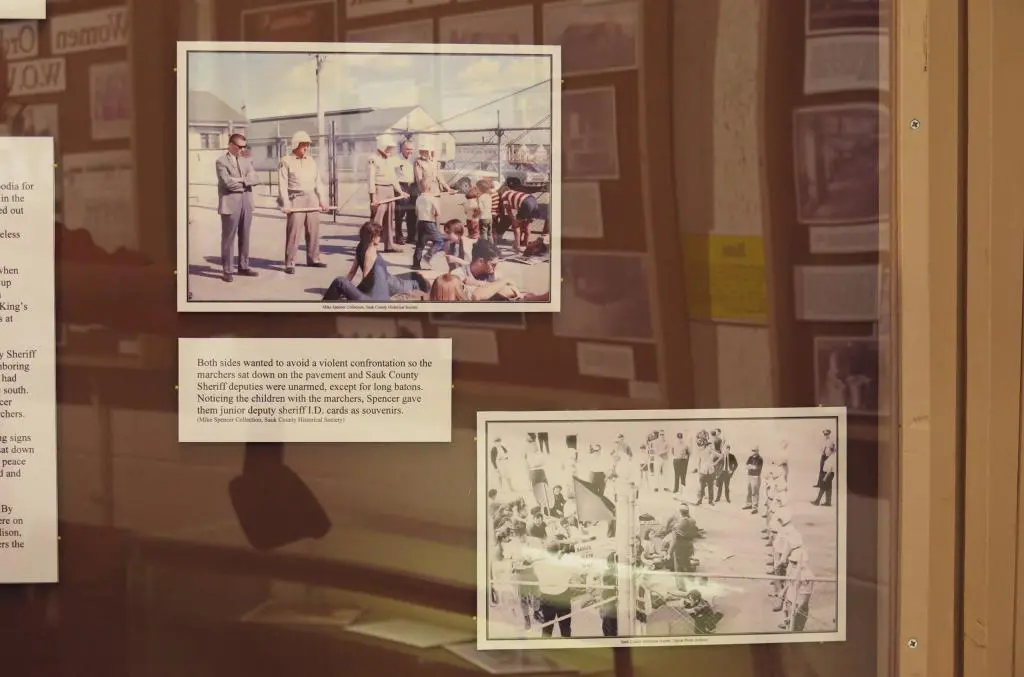

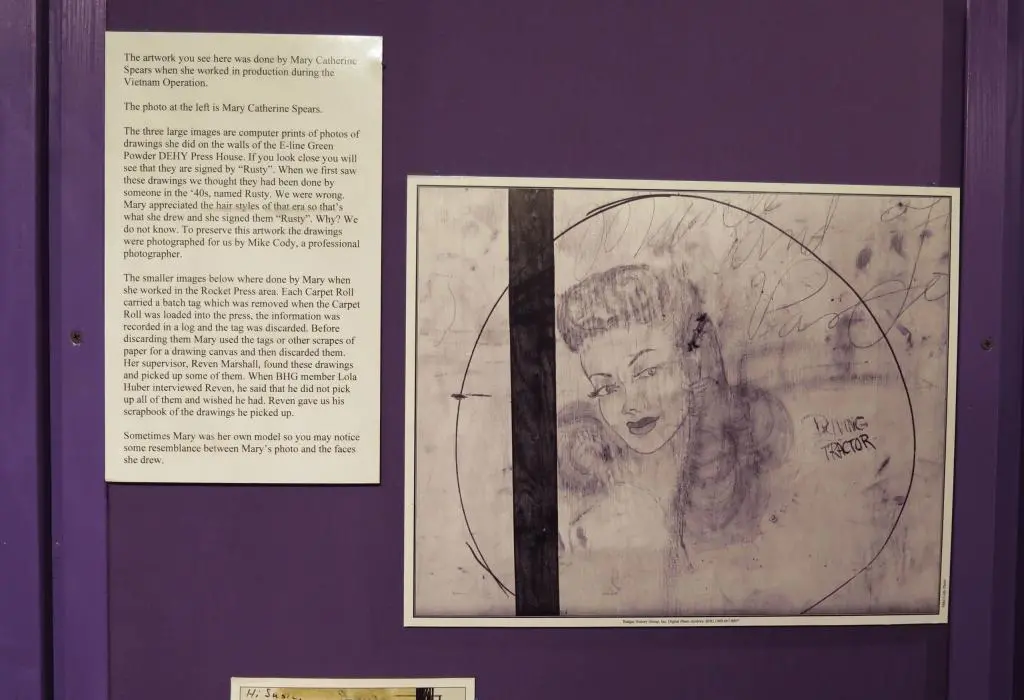

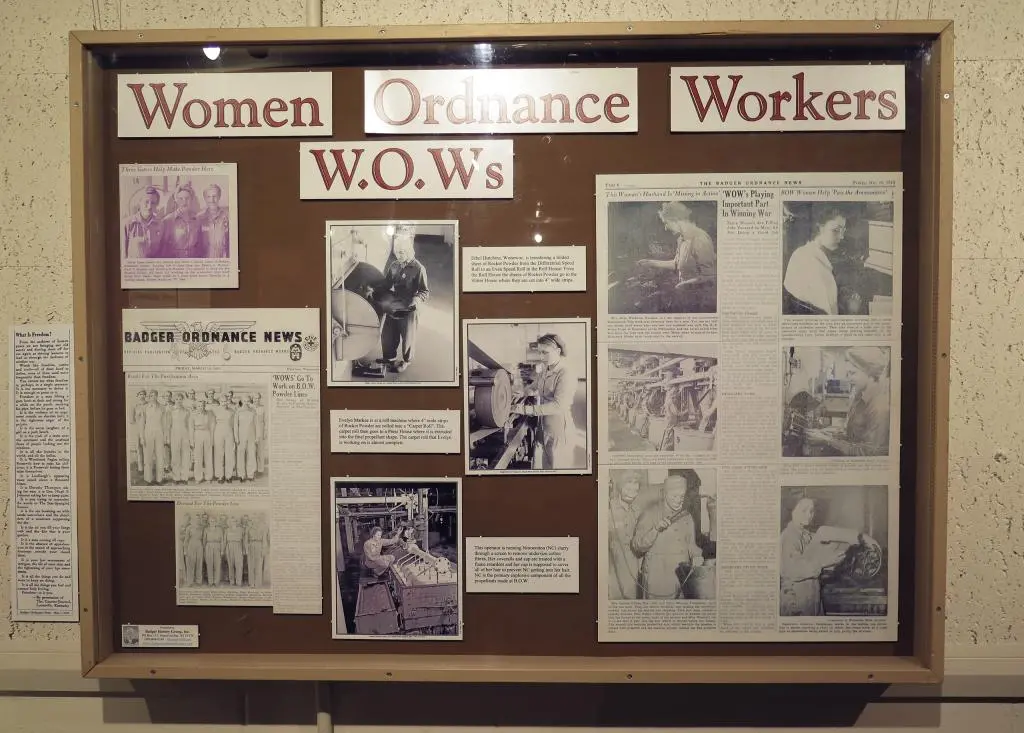

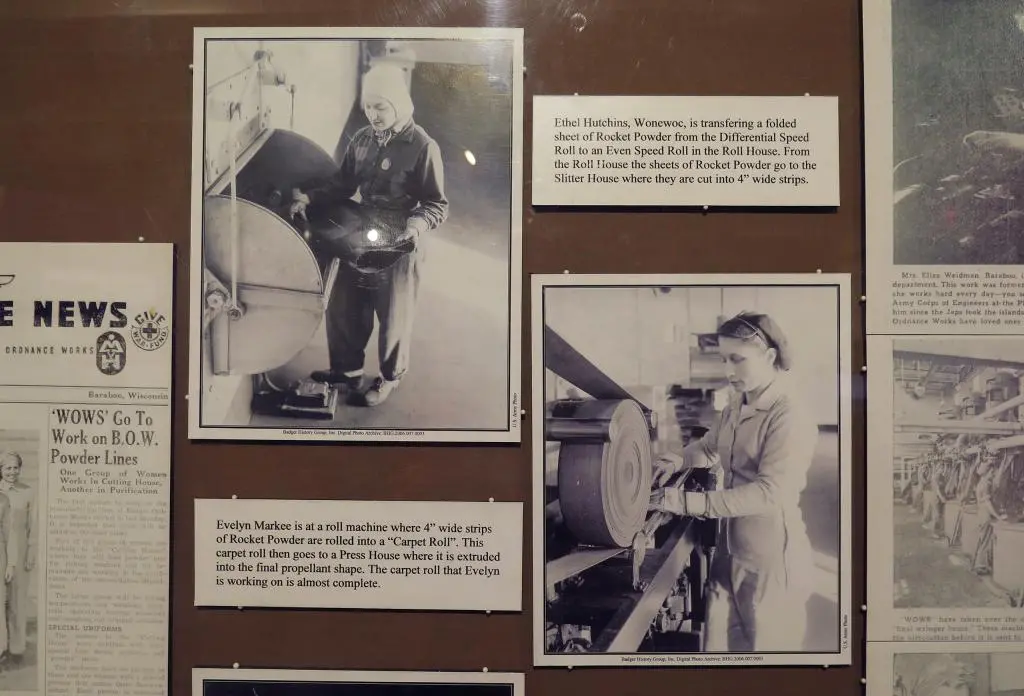

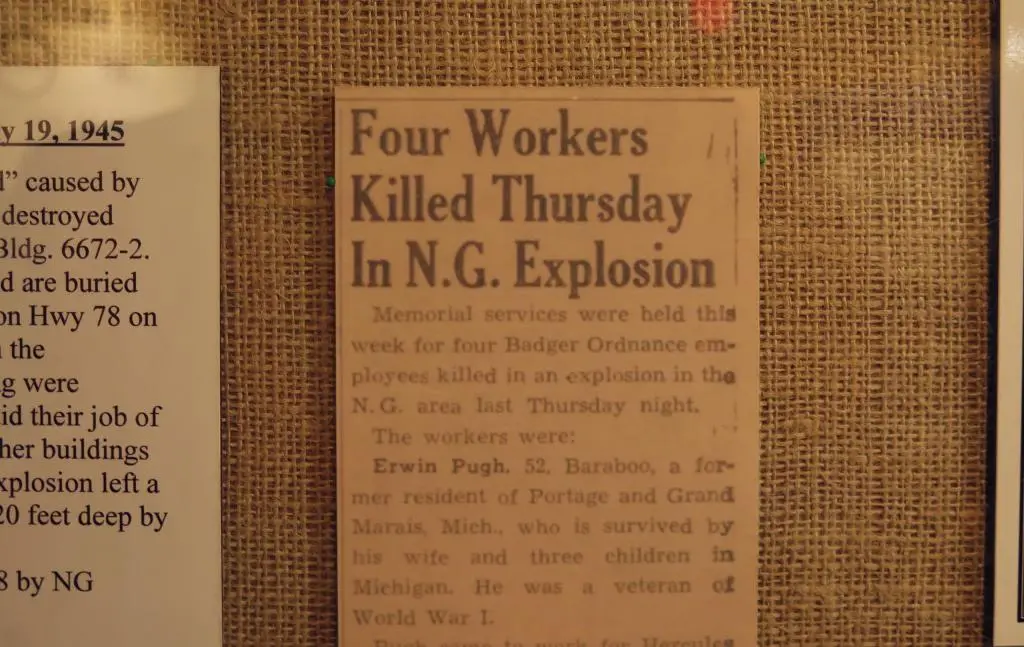

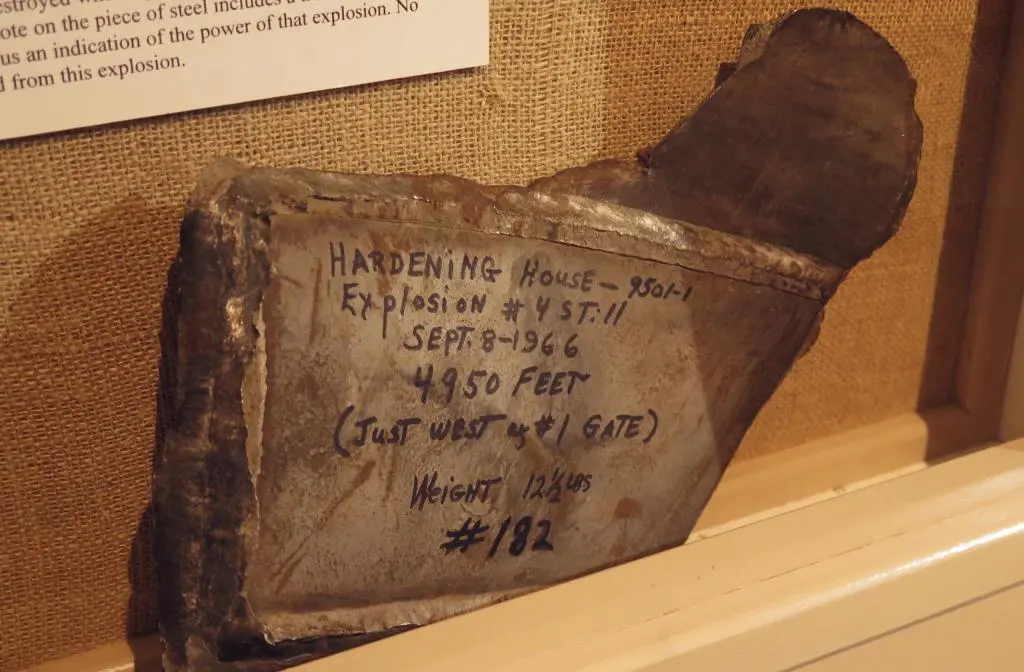

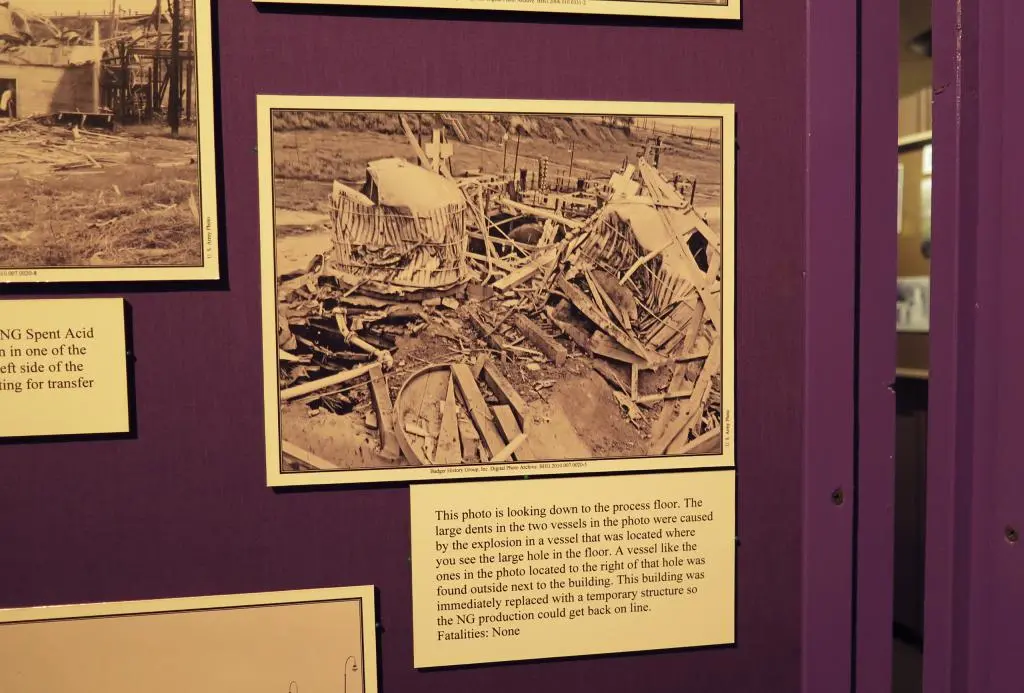

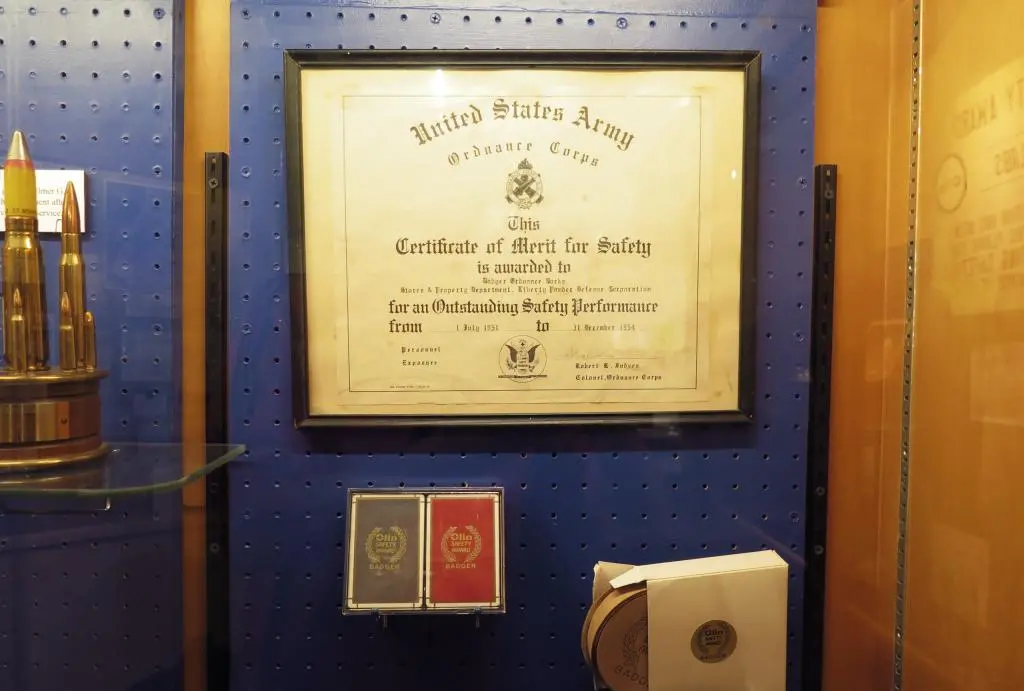

The museum was pretty fascinating. There were tons of photos taken during its operation, many relics from the buildings, and several displays showing the temperature of the times. While the plant's main use was for World War II, it was put into operation again from 1951 to 1957 for the Korean War, and from 1965 to 1975 for Vietnam. Protesters from UofM came up to the plant to protest in the late 60s.

The plant really only had those three major periods of operation. In 1977, the army put the plant on hiatus. In 1997, the plant was deemed unnecessary. A series of corporations exchanged control of the environmental cleanup and eventually demolition, which completed in 2013. The land was divided up mainly between the US Department of Agriculture, the Ho-Chunk Nation, and the National Park Service.

If I get a chance, it would be nice to return on a sunny day. I didn't explore too much because of the rain, and photos looked terrible. Although, I guess I'm not really sure what else I'll see. Search for cement foundations of buildings and take photos? It would be more interesting to take aerial photos.

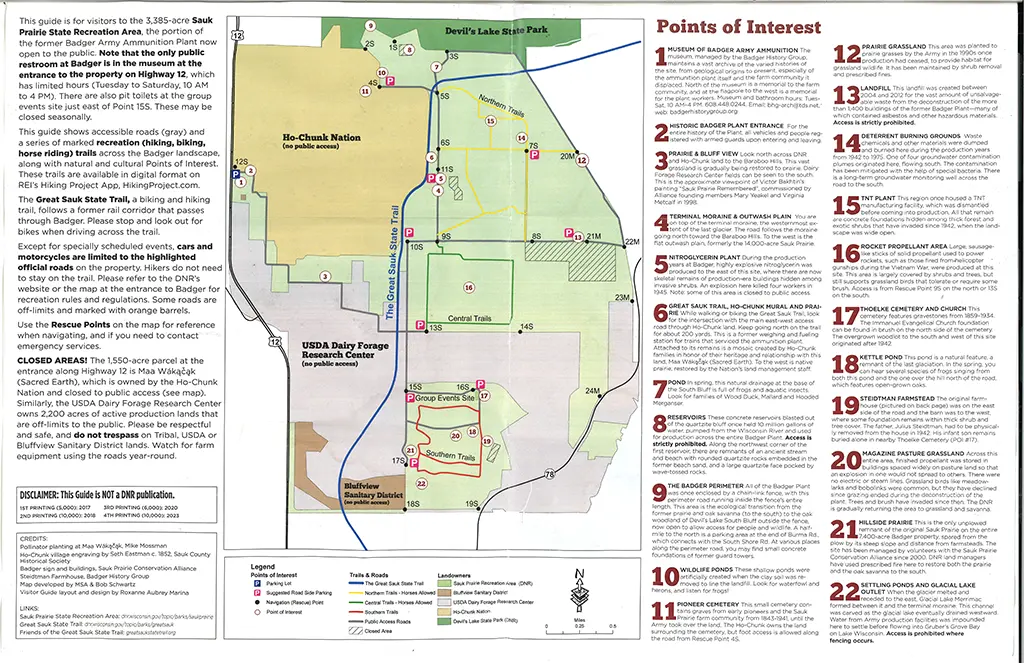

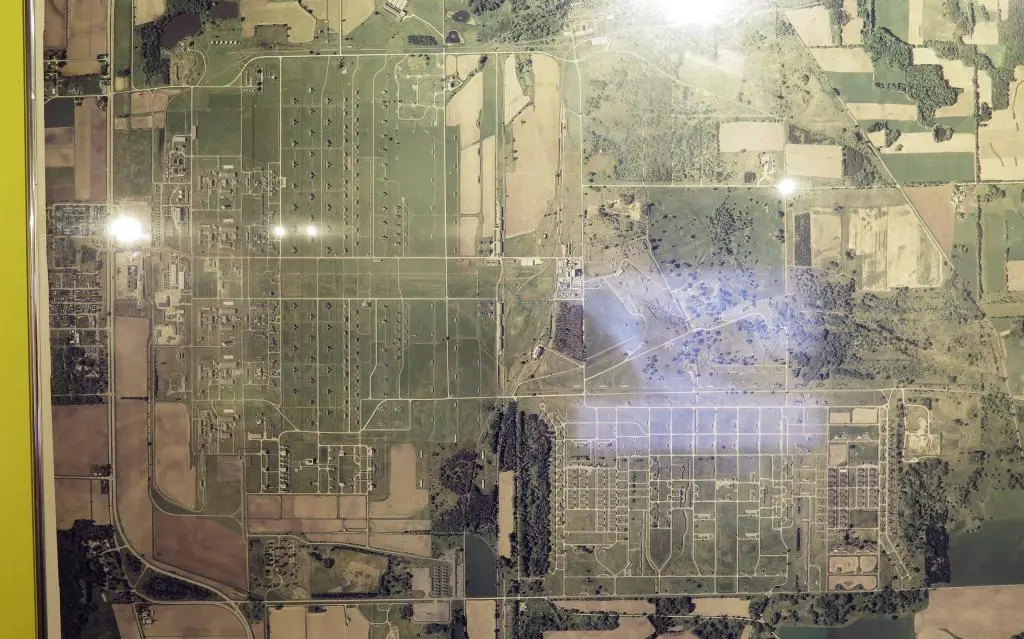

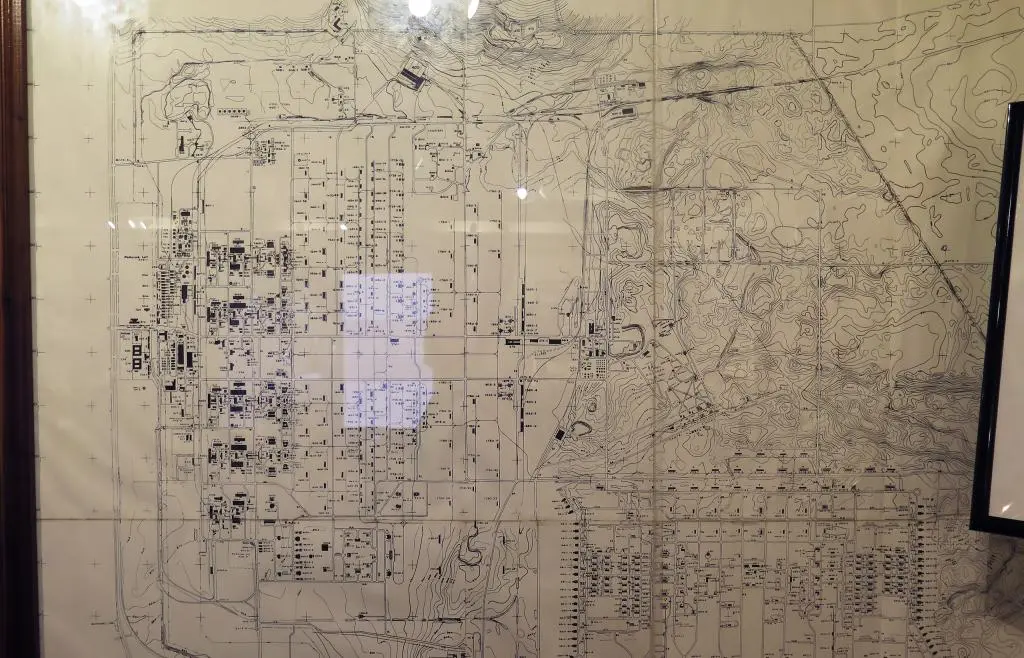

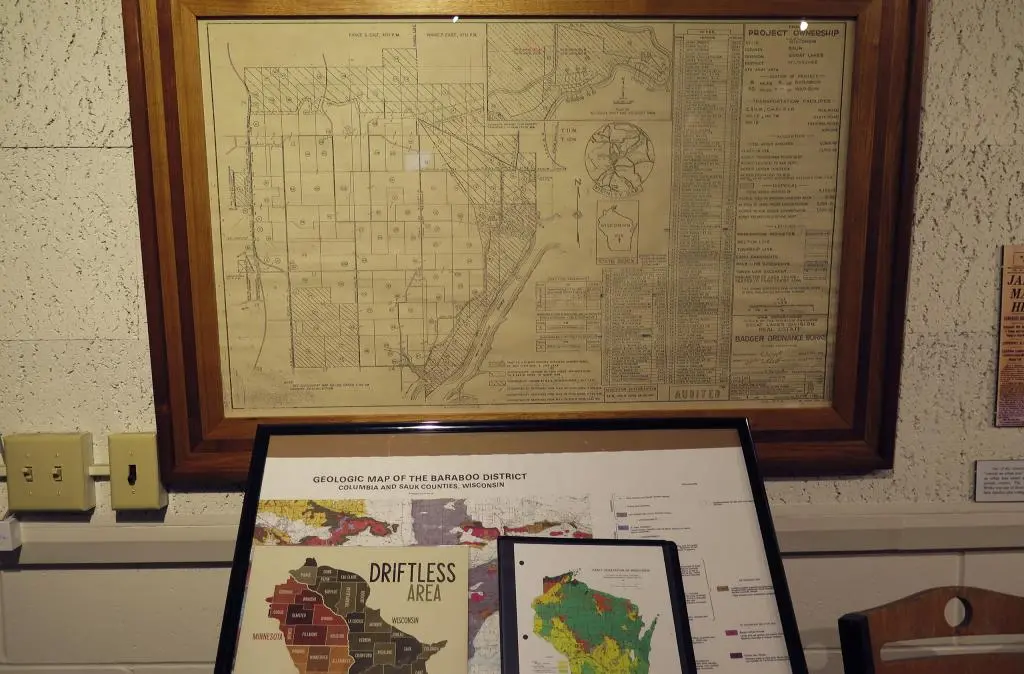

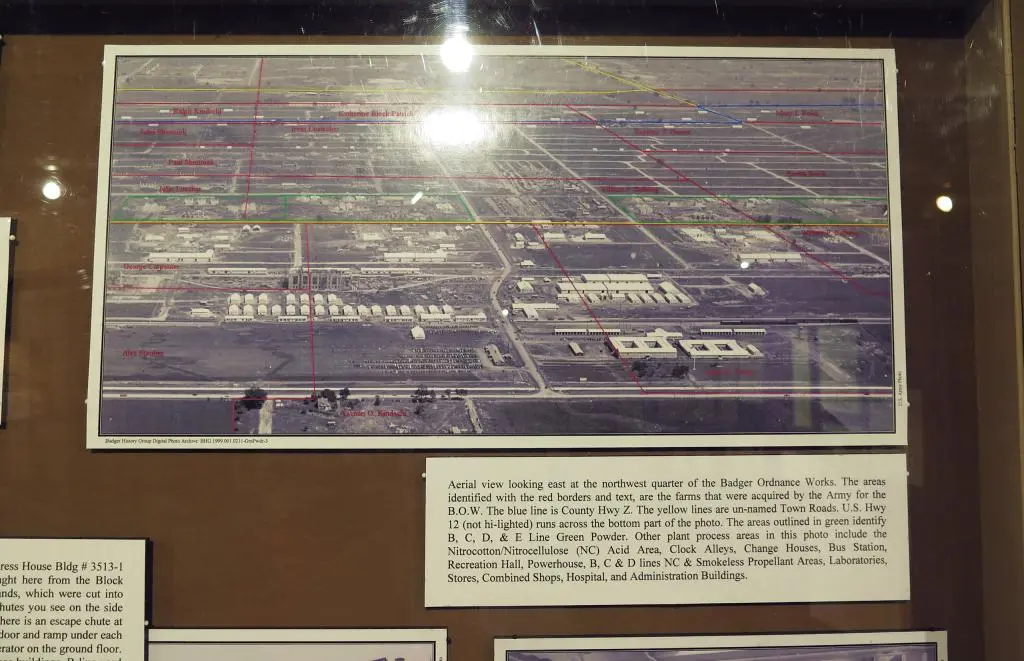

The badger museum and the entrance gateway had maps that I didn't fully study at the time. I think this map was an early version. Here's a clear one printed by the Sauk Prarie Conservation Alliance.

Looking at the map, you can clearly see how the land was divided. Also, there was so much much more to this area than I original thought. Those storage shelters were still only near the entrance. I didn't travel anywhere near any of the other points of interest listed here. I am too used to living in Japan where everything is so dense, so I did not imagine this area to be miles!

I think I will try to return next time I'm back in the states.

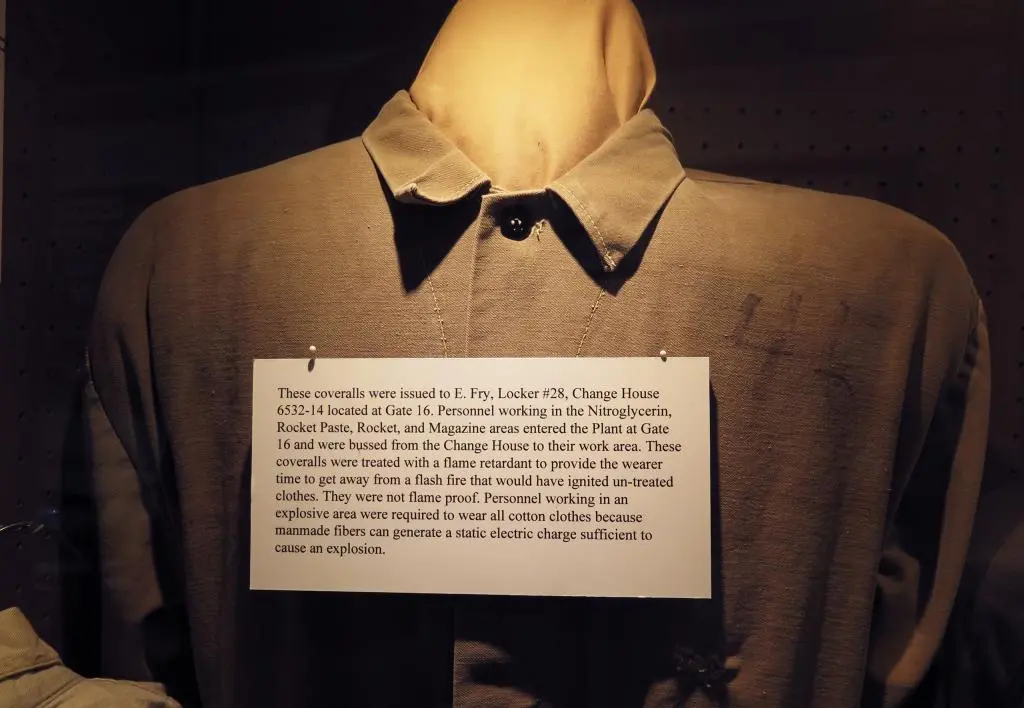

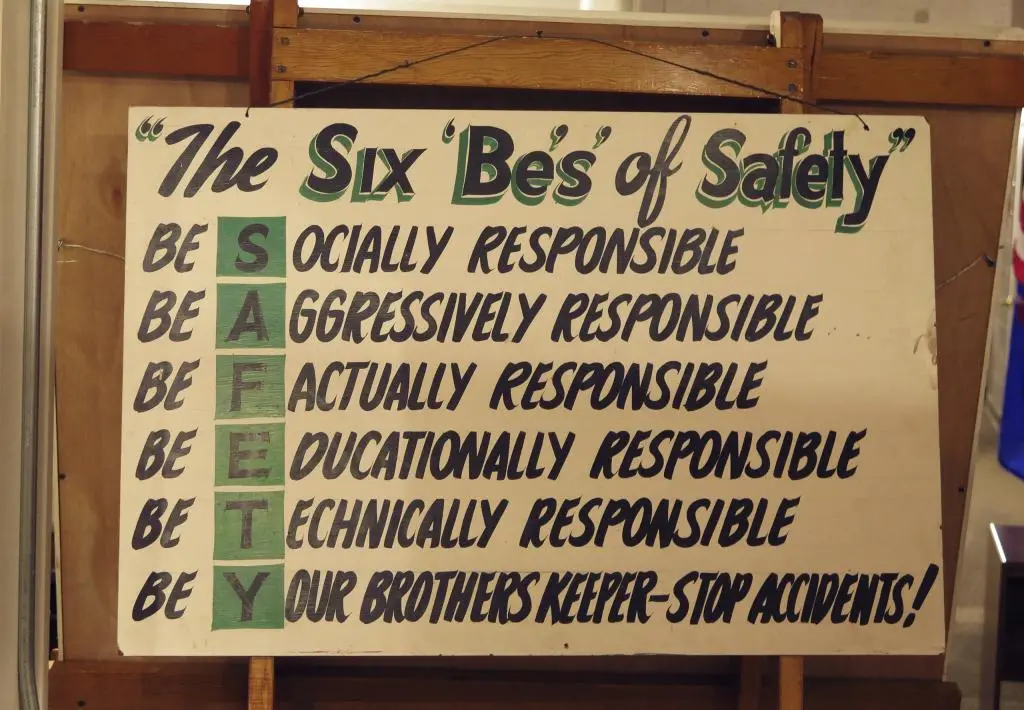

The museum was an excellent resource of the history of the plant and it was completely free. They sold some books and asked for donations, but it was not required. An old man was stationed there and talked a lot about the working conditions in the plant and safety. (I wasn't really paying attention, though, sorry.)

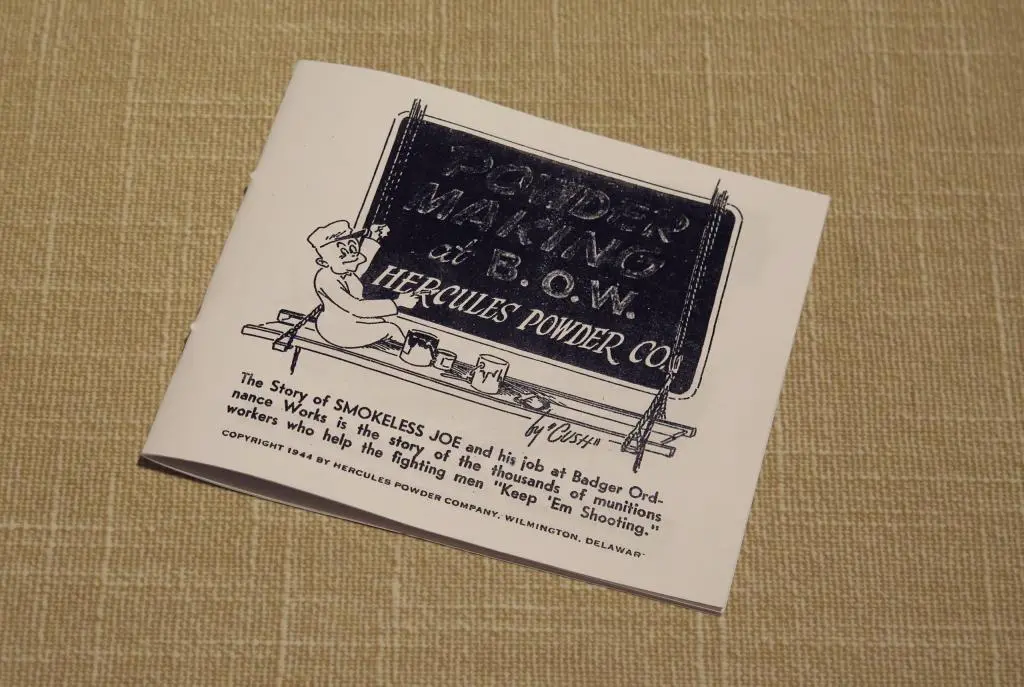

I grabbed some flyers on my way out, and scanned them when I got back home.

Badger Army Ammunition Museum flyer: gdocs/ badger_museum_flyer.pdf

Badger History Group flyer: gdocs/ badger_history_flyer.pdf

Badger Ammo Plant - A Different View: gdocs/ badger_plant_flyer.pdf

I'm not sure if I was supposed to take that last one. It seems like an original flyer from the 90s before the plant was decommissioned.

Overall, the museum had a far different vibe than any war museum I've visited in Japan (except for the Historical Records Office in Takayama). There was an overall underlying sense of pride of what was created here that never hinted at any guilt or responsibility of what would become of their product. All of the information seemed to focus on facts and presented the information like you could gleefully put yourself in the shoes of the workers.

I suppose when you "win" the war, you can gloss over the gravity of events that got you to the finish line.